The secrets behind fast fashion

Inside the factories that supply fast fashion companies lies a secret. The workers who were previously silenced are now speaking out for their basic human rights.

Fast fashion is an industry which is growing exponentially. Based on the principle of producing garments as fast as possible, it is fuelled by over-consumption. Accusations from within the industry have detailed how cutting corners to reduce costs, and high levels of waste have led to a detrimental impact on the environment and workers' rights being compromised.

Leicester, Birmingham and Manchester are all hotspots for fast fashion factories, which have been likened to Charles Dickens' novels for their characteristically bleak appearance and harsh working conditions. Leicester has the second-highest concentration of textile manufacturers in the UK, with 700 factories employing 10,000 textile workers. Recent reports from inside some garment factories have resulted in uproar amongst many in the city - and beyond.

Local factory workers have been reported to be earning as little as £3.50 an hour - £5.41 below the National Living Wage. A University of Leicester report found factory workers were often experiencing "excessive working hours, poor health and safety conditions in the workplace, and night shift subcontracting". The report goes on to explain the sinister side of factory work; "abuse, bullying, threats and humiliation, and a lack of toilet breaks", are commonplace.

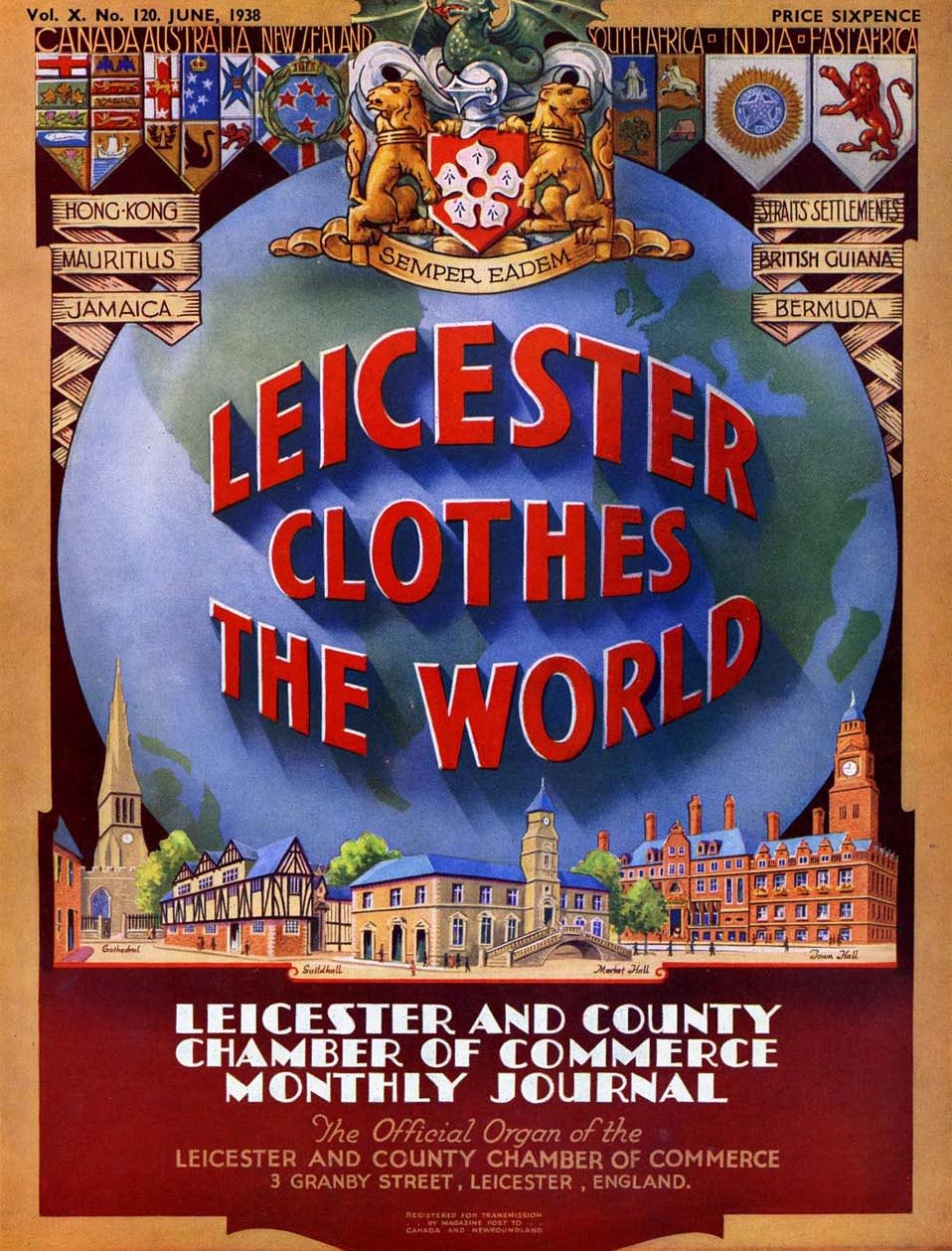

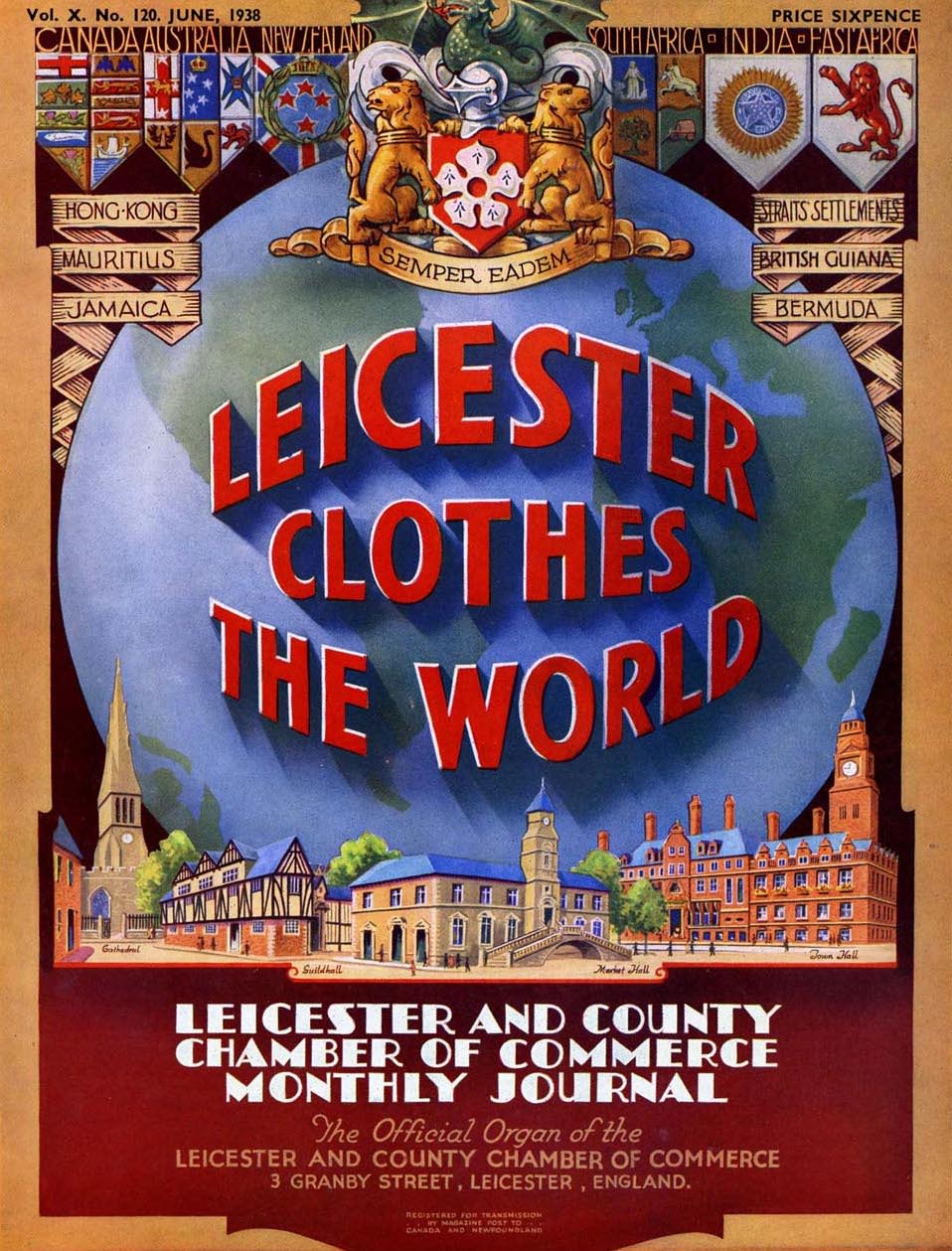

This front cover of the Leicester and County Chamber of Commerce Monthly Journal from June 1938 shows how intrinsic Leicester was to the textiles industry at the time.

This front cover of the Leicester and County Chamber of Commerce Monthly Journal from June 1938 shows how intrinsic Leicester was to the textiles industry at the time.

The fast fashion industry is a multi-billion pound industry. Fashion United released data on fast fashion retailers - it found Burberry to be the largest fast fashion retailer in the UK, valuing at over £10 billion. Next Plc, according to Fashion United, is the second-largest fast fashion company in the United Kingdom. It has a market value of over £7 billion.

The fast fashion company Boohoo Group Plc (Boohoo) has come under fire in recent months. The Boohoo Group includes many brands including Boohoo, Boohoo Man, PrettyLittleThing, Nasty Gal, Karen Millen, Coast and now Oasis and Warehouse - and in July 2020 it was estimated that 75%–80% of its clothing was produced in Leicester. The Levitt Inquiry, an investigation into Boohoo Group Plc's operations specifically in Leicester, found its factories to have unacceptable working conditions and underpayment of workers. It also found that Boohoo's monitoring of its Leicester supply chain has been "inadequate" for many years. Boohoo has since pulled production from over 60 Leicester-based factories as reported in December 2020.

The finger has been pointed in many directions - all with the aim of pinning blame on one particular group, but the question remains - who is responsible? Is it the factory bosses - the workers who are subjected to dire conditions sometimes blame their superiors for the alleged malpractices? Subsequently, the bosses often attempt to hold the retailers who order in bulk to account- a tactic designed to force suppliers to drive down their prices. Are the retailers to blame as a result of this practice? Or is it the government and the police who also been criticised for their alleged negligence in dealing with reports of bad conditions?

Since 2017, there have been nine callouts to fires in garment factories in the main Leicester LE5 textile district - including a large blaze in 2018, which caused the evacuation of nearby premises. It is clear that regulations are failing in Leicester - but at what cost?

The stories behind the factory walls

Factory workers have their say

Amina's story

Amina* grew up in the north of India. Childhood summers were filled with playing on the village soil with school friends and then rushing home for fresh food. She loved these simpler times; a childhood full of imagination and dreams. Unbeknown to her, Amina's adult life would prove tricky.

Amina immigrated to Leicester with her husband four years ago. The only work she had the skills to do was garment work - she worked in a Leicester fast fashion factory. She agreed to talk to me on the condition that full anonymity was granted. Her name has been changed to protect her identity. Amina talked to me in Punjabi, her native language. She says her choice to settle in Leicester was "the best decision" for her because she knew the industry heavily focused on textiles. Working in a garment factory was one of her very few options.

Coming to England for a better life was her motivation. A better life for her children of which she now has two. But the cost of this better life is bitter. She worked in dark factories where machines were holed away in small corners - her first introduction to this so-called 'better life'. One of the many things that will stay with Amina is the damp smell that overpowered the factory. It filled her senses and the small factory had little ventilation. Moreso, the material of the garments meant that the smell stuck to them, making it linger even if a window was cracked open. She left her work once the pandemic struck; the poor conditions made her feel unsafe, more now than ever.

Amina talks candidly about her time in the factory. The owners surveilled each worker with a watchful eye, sometimes demanding “faster, faster” in a bid to make workers more productive. Amina says that she felt like a slave; constantly being belittled if her work pace slipped. She’s akin to a machine to them she says, not a person.

“I did it for my children, they are all that matter to me and I have to work to feed them.”

A mother’s instinct is often overpowering of any fear she says. Amina felt like she had no choice. In order to stay in Leicester and pursue a better life for her children, she endured these conditions.

When Amina returned home from work her life remained difficult. She lives in a multigenerational house in East Leicester. Seven people in two rooms with one toilet. She says it gets very cramped. Amina misses her days in her home village as a girl. The days where space in the rural village was never an issue and life was easier.

Amina was paid £3 an hour at the garment factory, £5.91 below the National Living Wage. She says that she couldn't ask for a pay rise for fear of getting fired.

"I understand that I made the choice to come to England, but the way we are treated is despicable."

The likelihood of employers being inspected regarding their implementation of minimum wage is once every 500 years. Written evidence from HMRC shows that UK-based garment factory owners have been forced to pay out almost £90,000 to employees for non-payment of minimum wage.

The United Kingdom is the sixth richest country in the world. Amina thinks the better life she came for must only be for the natives of the country. "I have never known what it's like to be comfortable money-wise, I hope one day the UK will accept me and I will be able to get a fair wage."

These bleak conditions have been known around the world. In 2013 the Bangladeshi Rana Plaza disaster opened the world's eyes to the harmful conditions festering within factory walls. The Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing at least 1,134 people and injuring more than 2,500 people - it housed five garment factories. The International Labour Organisation said: "Most factories do not meet standards required by building and construction legislation. As a result, deaths from fire incidents and building collapses are frequent."

Amina now does sewing work at home - she says the pay is a little better but wasn't willing to tell me how much it was exactly. She sews and tailors in a small room. The walls are lined with garments - all of which she is proud of. She says she's "glad" she got out of the factory. "Doing homework means I have more time with my children now."

*Names have been changed to protect identity

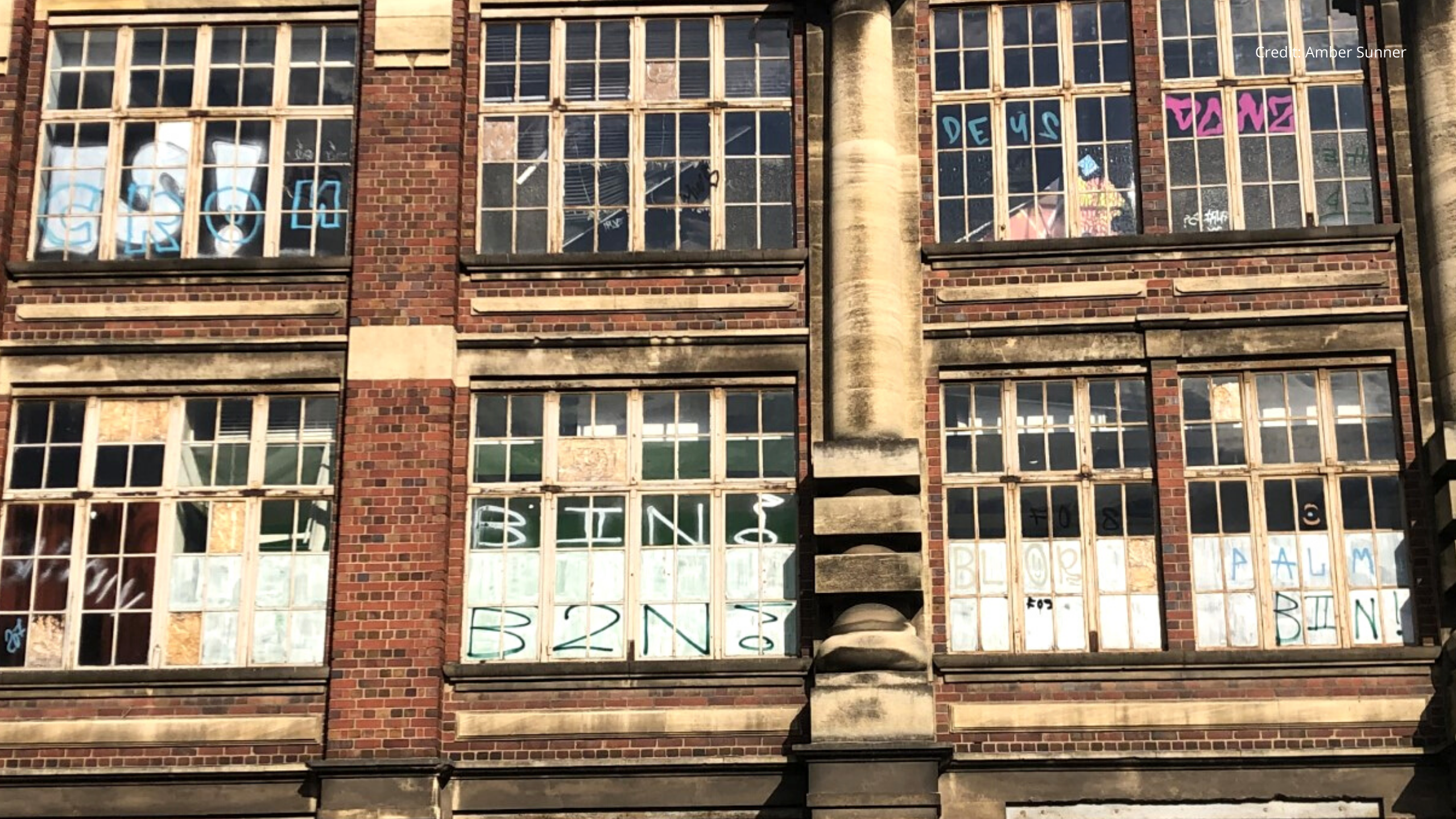

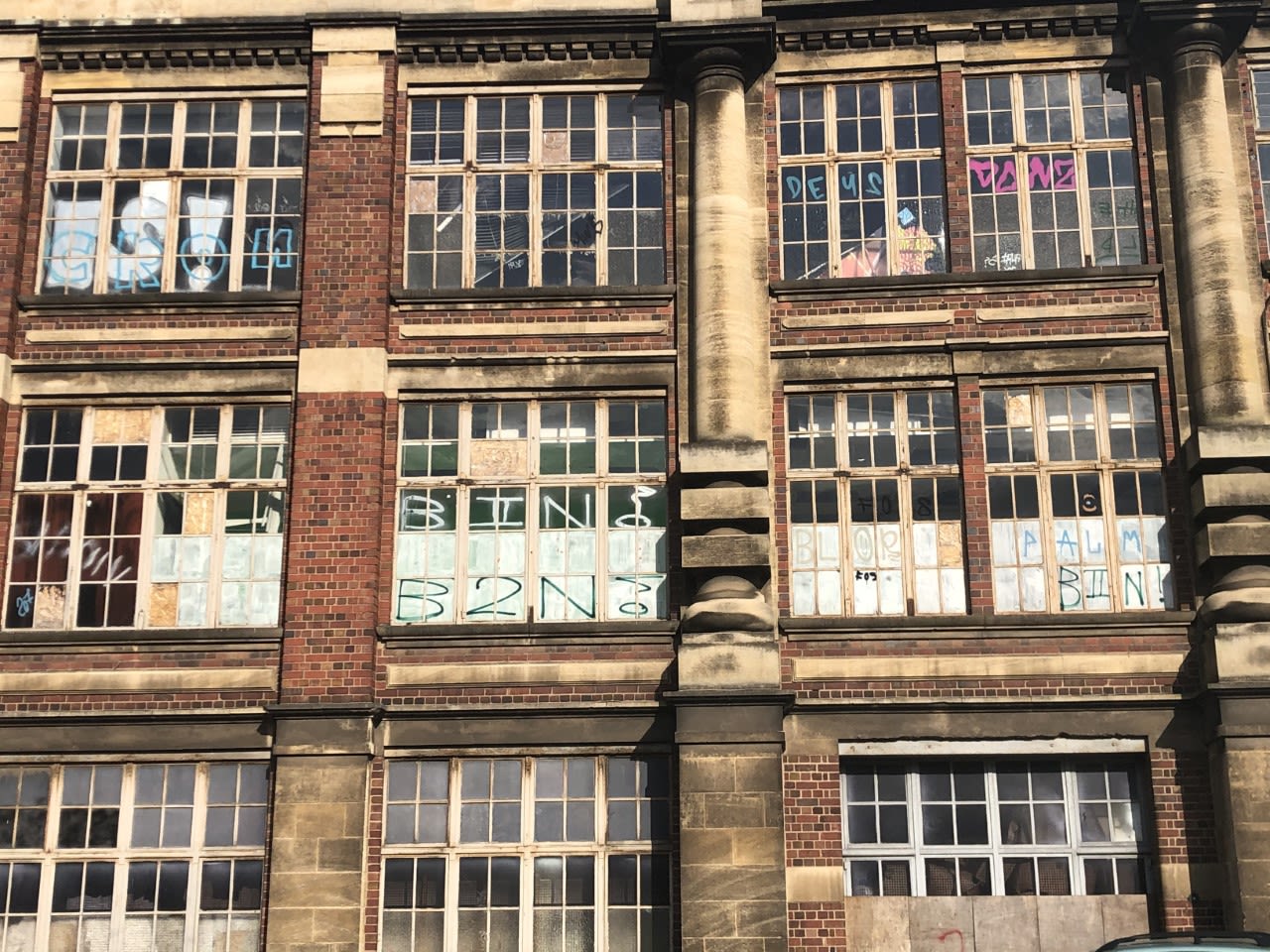

Credit: Amber Sunner

Credit: Amber Sunner

Saja's story

“I walked in and it was overwhelmingly hot – there was no ventilation, no windows either. It was in a dark basement.”

Saja Elmishri studied fashion at the University of Leicester. After she had graduated she interned in a Leicester garment factory in 2018. She quit after a few weeks because of the “unworkable” conditions.

“I made friends”, she says, “but we were forbidden to talk with each other”. The factory owner would keep a close eye on workers, ensuring maximum productivity and maximum profit. This often meant no small talk was allowed and Saja was often interrupted while getting to know her co-workers. Saja recounts a tense conversation between the factory owner regarding the productivity of workers.

"You have to be really quick to give the workers their materials," they said to Saja. In this case, Saja was in charge of the arms of a jumper product. They continued with the grim words:

“We think of the workers as machines. They need to work fast for me otherwise I won't be able to make money.”

The chilling exchange left Saja shocked and confused. “I couldn’t believe it; how can another human think of someone like that.” She was unaware of this treatment before she stepped into her first garment factory. The second one was worse.

“The entrance was clean and polished,” she says. "I thought this may be one that operates fairly." Saja's hopes were soon crushed once the boss took her down to the factory floor. “It was like I was in a different building. Another world entirely.”

Saja says she tried to remain positive despite seeing the poor factory conditions. "But I had a gut feeling that something wasn't right, here especially."

This hesitation was soon confirmed when she saw a pitiful scene. "One machinist had a poster of a tropical blue sea on the wall adjacent to work-station. They would sew and look up at the poster in a consistent motion - like they wished they were there.” Saja says the things she witnessed in this factory were "sweatshop-like"; an allusion to the deplorable conditions seen predominantly in South Asia.

Credit: Michael Lee on Unsplash

Credit: Michael Lee on Unsplash

Saja says she can deduce from her own reasoning that the workers had little choice but to stay and work in these Victorian-esque conditions. "If you have no other work being offered to you and no other form of income, it's often the only choice to work in such diabolical conditions."

Saja interned at a third and her final factory in Leicester. In this one, she was shown around by the factory manager. "The offices on the top floor were glossy and pristine, but history repeated. I was taken on the tour - again it was another story." Saja says the operation she saw was a "fraud". The factories she visited allegedly had 50 machines that cost £15,000 each, according to Saja. "They have the money for workable conditions, they just don't want to use it." Saja says the ceiling in this particular factory was crumbling - a very concerning sign.

As Saja progressed through the third factory the reality of the truly unworkable conditions became apparent. Each room got hotter and hotter the further she went in.

It makes Saja emotional to talk about her experience. Hundreds of garment factory workers experience these conditions every day. This is their reality being hidden in a city in the East Midlands. England’s 21st Century.

This insatiable need for maximum productivity is detrimental in all aspects, according to reports. A Human Rights Watch report found that "cutting corners" practices with the sole aim to bring down costs were rife in garment factories all over the globe. The report, titled Paying for a Bus Ticket and Expecting to Fly, found some common methods factory owners implement to get workers to produce more. Examples include: "Restricting workers’ toilet breaks; trimming their meal breaks; disallowing drinking water breaks and other rest breaks."

These stories offer an insight into the reality of some fast fashion factories - and the urgency for change is evident.

History of the industry

Leicester has a rich industrial heritage. Post-war Britain saw the manufacturing of shoes and clothes boom as the city became a hub for this activity. The industry's transformation to the alleged deplorable conditions recounted today was a gradual one.

The people fighting for change

Campaigners are calling for changes to be made to the garment industry

Boohoo Group Plc reported a £92 million profit in the year ending February 2020, with a 44% increase in annual revenue. The multi-million pound company has been accused of treating workers poorly and hosting working conditions below par.

With bad publicity about injustices like those recounted by Amina and Saja - changemakers often arise. One of these is the campaign group Labour Behind the Label. The group found in a report titled Boohoo & COVID-19: The people behind the profit that garment factories provided a means of illegal work for immigrants, particularly if they do not have permission to be in the UK or are seeking asylum - so are not permitted to do paid work. With 33.6% of garment workers coming from outside of the UK, some reports have called them vulnerable and have linked this to their exploitation in factories.

Campaign Manager of the group, Meg Lewis, said: "The conditions in Leicester are not a secret. It's even been nodded to in government documentation."

She said the problem was not just confined to Leicester but is becoming more widespread across the whole of the UK. "The pandemic has exacerbated the existing issues inside the factories - especially in Leicester. "

Meg said the failings are layered - a culmination of different alleged malpractices accounted for the problems in Leicester's garment factories. "There's not one person accountable, I think accountability should be shared for the gross misconduct seen in the garment industry in Leicester and around the UK."

Meg lays out what the campaign group wants one fast fashion retailer, Boohoo, to do to help work towards overcoming the issues seen in garment factories.

Boohoo has made progress in terms of accountability - such as publishing a comprehensive supplier list in March 2021. Meg says, however, that the way Boohoo treated its workers in the pandemic took things "to a new level".

Boohoo made the headlines in local Leicester news and national news over the pandemic. Reports emerged that during the coronavirus national lockdown, the company's Leicester based factories consistently flouted rules and guidelines, causing their workers to be at a greater risk of catching the deadly virus.

Meg said the pandemic has created a tendency of blame towards one particular group - factory owners. "Companies such as Boohoo have tried to distance themselves from factory owners - it's simplistic to think that there is only one failing."

"People were forced to risk their health and their livelihoods just to make a living." The cause of this extreme exploitation according to Meg was the purchasing practices being carried out by Boohoo. "In order to make that huge profit brands will demand lower and lower prices from their suppliers, and they will demand much faster turnaround times," she said.

This tactic is what Meg thinks was the big driving force behind the exploitation of workers in Leicester. "This kind of practice can be seen across the world. So whether we're talking about production in Bangladesh or India, or as we can see production in the UK - it often has the same tune."

A colossal $3.19- $5.79 billion (US) is owed to garment worker across the globe according to the Clean Clothes Campaign - a total which accounts for the first three months of the pandemic only. The figure encompasses the number of cancelled orders which rocketed as the pandemic hit. A new campaign has since emerged after these figures were revealed. The #PayUp campaign has made great strides in retrieving money - helping suppliers recover an estimated $22 billion in cancelled orders.

"When the pandemic hit Europe and the US, and more and more stores were closed, brands and retailers responded as they usually do: by pushing the risk down the supply chain."

These kinds of underhanded tactics are now being exposed on social media to spur global change.

BANGLADESHI GARMENT WORKERS ARE BEING EXPLOITED, ABUSED & FORGOTTEN AND NEED OUR HELP. 🇧🇩

— Nabela Noor (@Nabela) July 2, 2020

Please take 2 minutes to watch this video. RT & tag the brands + people involved.

4.1 million Bangladeshis are at the brink of starvation + homelessness.

IT IS TIME TO #PAYUP. pic.twitter.com/aGHi0bncow

Credit: @Nabela

Retail company Edinburgh Woollen Mill has recently come under scrutiny for such moves. They have allegedly refused to pay in full for their orders and have been intimidating their suppliers according to the Clean Clothes Campaign website. The retailer is owned by Dubai-based British billionaire Philip Day. The company has been approached about the allegations but has not commented on them publicly.

Credit: Clean Clothes Campaign

Credit: Clean Clothes Campaign

The Secretary of the Leicester Unemployed Workers’ Centre, Mark Mizzen, said the reasons why underhand tactics are allowed to occur was due to local support services being decimated as a result of austerity cuts. "For example, there is now no full-time provision of Social Welfare Law Advice (welfare rights) in the Highfields area due to government austerity cuts and yet there is many tens of millions of unclaimed entitlement and tax credits in the Leicester area," he said.

Mark spoke of how the problem was being tackled: "Local community organisations led by the Highfields Centre (Highfields Community Association) have teamed up with the local trade union movement with the Leicester Unemployed Workers Centre to help forge change."

Mark talks about the deep-rooted inequalities seen in the garment factories and how Leicester authorities were working to solve this entrenched issue.

Third-party audit reports found Boohoo to be selling clothes made by at least 18 factories in Leicester that auditors say have failed to prove they pay the minimum wage to workers, according to The Guardian.

Boohoo responded to this information saying that it “appears to be a selection of commentary from a limited number of the third-party audits that have been completed”.

Mark said: "I hope Leicester City Council will focus on enforcement. My concern is that this approach may attack the very workers it is supposed to support." Mark goes on to talk about the power trade unions could wield if they were allowed to intervene in the matter and enter factories to talk to the workers.

This idea is not new - many have been pushing for the same solution. Sir Peter Soulsby - Mayor of Leicester - called a meeting with the aim of bringing together the retailers and the trade unions to get the action needed to resolve the issue.

This call, also supported by the regional secretary of Trade Union Congress (TUC Midlands), Lee Baron, was made via an open letter to the CEOs of nine fashion companies. The list includes Arcadia Group, ASOS, New Look, Quiz, Boohoo, Next, River Island, Missguided and TK Maxx.

The letter addresses the issues in Leicester's factories specifically. It reads:

"We are aware that efforts have been made to implement auditing systems to ensure that factories are complying with basic requirements of employment law, but these have clearly not been successfully implemented universally and too many people remain employed across Leicester with sub-standard terms and conditions."

The letter was in addition to a round-table summit hosted by Sir Peter in a bid to encourage "all employers to sign a TUC agreement committing these retailers to procure from manufacturers who recognise and work with trade unions," according to the TUC website.

Andrew Bridgen, MP for North West Leicestershire said last year that he believed there were approximately 10,000 people in the UK’s clothing industry being paid £3 to £4 an hour in conditions of modern slavery.

“If there was a fire there then hundreds would die, and this is Britain in 2020. It’s a national shame.”

TUC's Campaign Support Officer, Rob Johnston, talked about how the trade union model - a model that involves garment workers joining trade unions to represent them - would help to eradicate the problems seen in various Leicester factories.

The impact of Leicester's tarnished reputation is being felt already. Companies like Boohoo Group Plc have pulled production from over 60 Leicester garment factories. A Boohoo spokesman declined to say how many businesses had been cut. As a result of this move from Boohoo Group Plc, workers are losing their jobs entirely and the entrenched problems are not being rooted out effectively.

Rob explained the effect of such a big change to garment district on a city like Leicester.

The Senior Joint Head of Highfields Centre, Priya Thamotheran, said in October 2019 a meeting set up by the Ethical Trading Initiative was hosted in the centre. The meeting was attended by the ETI, various trade unions and clothing brands. Priya offered solutions to the conditions being endured in some Leicester factories. "I suggested building connections with garment factory workers to begin to build up trust and confidence. This was in order to propel action to address whatever issues they were facing, whether that has to do with paid holiday, the working conditions and so forth."

These recommendations were set to be implemented in January 2020. Priya and his team left feeling hopeful of the changes set to be made to Leicester's garment industry. Instead little came of this meeting. Slowly - one by one - each brand dropped out. By February 2020 Priya was informed that the last brand at the initial meeting had dropped out. The reason given to Priya was disheartening for him to hear.

"They said that Leicester textile factories were too tough for them to continue the linkages," he said.

Credit: Amber Sunner

Credit: Amber Sunner

Priya said if the recommendations from his team had been implemented as planned in January 2020, Leicester would be perceived in a flattering light sans this pandemic-driven tarnished reputation. "A lot of agony and pain could have been saved if that project had gone ahead because, in the absence of such an initiative, talk of how 'bad' Leicester is will continue."

Priya and his team were ignored by major brands - showing how rife contempt is in the industry. "We were saying something needed to be set up, where that essential trust and confidence could have been built up between our development workers and the factory workers to begin to work out these issues." Ultimately, these calls were ignored.

Leicester's Deputy Mayor, Councillor Adam Clarke, also attended these meetings. He talked about the devastating impact of losing fast fashion factories in Leicester.

"If Boohoo moves off the scene somebody else could move into that space and not change their practices or nobody will move into that space and Leicester loses trade. It's a lose-lose situation."

He talked about the potential lasting impact if the industry was to move out. "I want to drive out every bad job in the city, but we need the industry to stay because if they move out, exploitation will most likely occur elsewhere."

Despite the Boohoo Group recently pledging a series of reforms, including reducing the number of factories it relies on and using new ethical suppliers, Cllr Clarke says the situation is still difficult to manage for the City Council. The council had raised numerous concerns to the government but the action from the latter was very much lacking.

Cllr Clarke said that a non-judgemental and safe environment for whistleblowers is fundamental in rooting out the issues in the factories. "This is key for Leicester going forward - there can be fear in communities. There is some fear of authority -whomever that authority is—in those communities. It is a real challenge to create that non-judgemental environment."

He continued, saying that the City Council was working towards creating a space like this with the Slave Free Alliance, Citizens Advice Bureau and other voluntary sector organisations.

Credit: Kate Peters

Credit: Kate Peters

With 93% of brands surveyed by the Fashion Checker not paying garment workers a living wage, government complacency as Cllr Clarke outlines, is not the right step for those who are suffering. Fashion Checker states: "The majority of garment workers are unable to afford life's basic necessities. Fair pay for labour is a fundamental human right, but none of the biggest fashion brands pay garment workers a wage they can live on."

This outlines the extremity and urgency of the issue. Brands seem not to be listening attentively to the outcries from campaigners, as it was revealed last year that the likes of Fashion Nova, Boohoo, Revolve, Pretty Little Thing and Forever 21 all scored less than 10% on the Fashion Transparency Index (FTI). The FTI is a product of Fashion Revolution - the world’s largest fashion activism movement.

Co-founder and creative director of Fashion Revolution, Orsola de Castro, said: "What we do know for a fact is that those responsible for the wellbeing of those people i.e. their employers knew of the conditions the workers are facing. That is what is important because they absolutely knew and they did nothing."

Credit: Kate Peters

Credit: Kate Peters

War on Want, an anti-poverty charity campaign that aims to uplift garment workers, demands accountability from UK clothing brands, and is asking for globally binding agreements to protect workers throughout the supply chain.

Senior Economic Justice Campaigner at the campaign, Owen Espley, talks about the difficulties of tackling the issues head-on.

Supervisors who answer the door to enquiring journalists have been known to say that they are not allowed to speak to them. “We are busy and have to work now. I’m not allowed to discuss any matter about it,” one said to a Guardian journalist.

Multiple Leicester-based factory owners who had bad practice allegations were approached for this project; no comment was given. Insolvency Service data revealed more than 50 factory owners of clothing manufacturers in Leicester had been struck off for a combined total of more than 400 years in cases costing HMRC millions. One of the main reasons for their bans was due to minimum wage issues.

Changemakers are battling for progress - and it is working slowly. Their campaigns are chipping away at retailers and noise often leads to action. Breakthroughs are occurring but more pace is evidently needed to help the workers as efficiently as possible.

Government action

The government have come under intense scrutiny for poor factory conditions in areas like Leicester. But how have they responded to the scrutiny?

Government action has been sparse in terms of actively combatting and controlling the poor working conditions in Leicester. Boohoo Group Plc CEO, John Lyttle, asked the government to take a more active role in “protecting people being exploited in UK garment factories” in a letter to Home Secretary Priti Patel.

Cllr Clarke also called for more government involvement in the matter. He said that the government were "sitting on their hands" when it came to actively sorting out the issues in Leicester.

The Environmental Audit Committee launched an inquiry into the fashion and garment industry in the UK. The committee started its work in 2018 and the following year presented its recommendations to the government in its report titled: Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. The government rejected most of these changes - which included giving more responsibility to producers of garments and due diligence checks across fashion supply chains to root out forced labour.

The committee specified the area of Leicester as of high concern. "The Covid-19 pandemic has shone a light on garment factories in Leicester. Reports of poor working conditions suggest there has been little improvement since the Committee’s report, which recommended regular audits and for companies to engage with unions for their workers."

The report found that poor pay and conditions are standard in global garment supply chains according to evidence submitted by the global trade union IndustriALL.

The union represents those who work in the manufacturing industry. It found that over 90% of workers in the global garment industry have no possibility to negotiate their wages and conditions and so are unable to claim a fair share of the value that they generate. The union argues that Corporate Social Responsibility (a self-regulating business model that helps businesses be socially accountable) has failed to address the problems of poor working conditions and low pay in the garment industry through its programmes.

The report also cites this shocking evidence:

"A 2016 report into Corporate Leadership on Modern Slavery found that of 71 leading retailers in the UK, 77% believed there was a likelihood of modern slavery occurring at some stage in their supply chains."

Evidence was submitted to the report which indicated that a fire door in a Leicester factory was padlocked shut. The city has also been identified as having a high concentration of human trafficking according to the Stop the Traffick coalition’s Centre for Intelligence-Led Prevention (CfILP). The campaign coalition found abuse in the garment industry among other sectors.

The Fixing Fashion oral evidence meeting was held on the 16th December 2020. It collected the voices of the most influential powers in the fashion industry.

One of these voices was the Senior Policy Adviser of the Traidcraft Exchange charity, Fiona Gooch. She explained that accountability should be shared beyond the factory owners, saying that the purchasing practice culture of retailers of buying cheaper garments from suppliers was a leading cause of the issues seen in the industry. If suppliers - the garment factories producing the goods - are in a price war with other suppliers, then they are forced to drive down their costs which leads to malpractice arising, according to Fiona. She added that fast fashion retailers often want the cheapest supplier to maximise their own profits.

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

The International Labour Organisation estimates 86 million garment workers are in severe hardship around the world. Fiona expanded on this point in the committee hearing. She said: "Often garment workers are the main breadwinners of their family and they can now no longer pay rent, they cannot buy food, they cannot pay for their children’s education, much less medical care, given that we have Covid." She continued, saying many garment workers were working in very unsafe conditions both internationally and in Leicester.

Fiona added that these issues could not be solved by voluntary action. "It is not possible to persuade retailers to change their abusive purchasing practices. Sixteen thousand people campaigned with Traidcraft Exchange, asking the brands to pay up."

She said these efforts along with the Prompt Payment Code (defined as the gold standard in payment terms and plays an important role in bringing about a culture change in payment practices) were ignored - despite the media exposés. She suggested, on behalf of Traidcraft Exchange, that a regulator in the form of an adjudicator and licensing was a viable solution.

An adjudicator, in this case, would operate as a body that could carry out independent investigations and challenge companies to focus on priority areas, to help "curb abusive purchasing practices". Fiona added: "There is no action in this space at the moment. We need it for a level playing field."

Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority's (GLAA) Head of Enforcement Ian Waterfield commented on the allegations against some Leicester garment factories. “No one should have to work in an unsafe environment, feel forced or coerced into doing so, nor have their labour exploited." He said such behaviour would not be "tolerated" and that a multi-agency drive was ensuring such practice was tackled.

He asked for a better dialogue from exploited workers.

“We want to know about unsafe working conditions, businesses that are exploiting their workers, employers who are committing tax fraud – we want people to feel confident to report their concerns.”

Priti Patel described the alleged working practices as “truly appalling”, and called on the National Crime Agency (NCA) to investigate. “Let this be a warning to those who are exploiting people in sweatshops like these for their own commercial gain,” she said. “This is just the start. What you are doing is illegal, it will not be tolerated and we are coming after you.”

Credit: Kate Peters

Credit: Kate Peters

Police perspective

The National Crime Agency has teamed up with the Leicestershire police to help resolve the issues

The National Crime Agency (NCA) launched an investigation into modern slavery after the poor conditions of some Leicester factories were exposed. The NCA joined forces with many different groups - the Leicestershire Police, the tax office (HMRC), Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), the Health and Safety Executive, Leicester City Council, Leicestershire Fire and Rescue and Home Office Immigration Enforcement. Although the findings of the investigation will not be published, the NCA said they would "respond to partners on an appropriate level".

The agency said in a statement regarding the investigation: "Our primary focus is on the protection of vulnerable people and safeguarding them from harm."

Operation Tacit - led by the GLAA - an executive non-departmental public watchdog - aimed to uncover clandestine practices in Leicester factories by conducting unannounced visits to the suppliers. The operation is in response to the allegations that emerged over the coronavirus pandemic.

The watchdog has not found evidence of modern slavery to date, as previous allegations suggested, but it has found evidence of workers not getting the national minimum wage, as well as inadequate welfare.

While work continues on Operation Tacit, an update showed that the task force has, to date, visited 143 of the 232 premises of interest to them. 24 of those visits have resulted in issues being uncovered leading to enforcement action being taken by agencies involved in the task force. Issues in these 24 factories ranged from health and safety issues, unsafe working practices and issues surrounding Covid-19, social distancing and illegal working.

The Ethics, Integrity and Complaints Committee - set up to scrutinise the behaviour, standards and integrity of Leicestershire Police by members of the public - focused on the issues in one meeting. It said: "Tackling labour exploitation, especially with the garment sector is complex and multi-faceted. Although the word “exploitation” is used regularly to describe such issues, it is not criminal exploitation in the way it is legislated for within the Modern Slavery Act 2015"

On the 22nd December 2020 Leicestershire Police arrested seven people in the city as a part of the modern slavery factory probe. This signals that change is occurring, but will it be kept up?

Credit: Canva

Credit: Canva

Credit: Canva

Credit: Canva

Retailers' response

Retailers such as Boohoo are being proactive in making changes to their supply chain model

Boohoo Group Plc responded to the allegations accusing them of malpractice uncovered in various reports. The group said in a statement to its board that they were "shocked and appalled" by the allegations - but what are they doing to rectify these long-standing issues?

The group issued an independent review into its Leicester supply chain. Conducted by Alison Levitt QC in September 2020, it stated Boohoo's monitoring of its Leicester supply chain was inadequate and that the allegations about "poor working conditions and low rates of pay in many Leicester factories are not merely well-founded but substantially true".

Credit: Amber Sunner

Credit: Amber Sunner

However, Ms Levitt found: "The problems in Leicester are complex and of long-standing and Boohoo is not solely to blame; others too are responsible for not having gripped this over many years." Ms Levvitt made many recommendations to Boohoo Group Plc, all of which the company accepted.

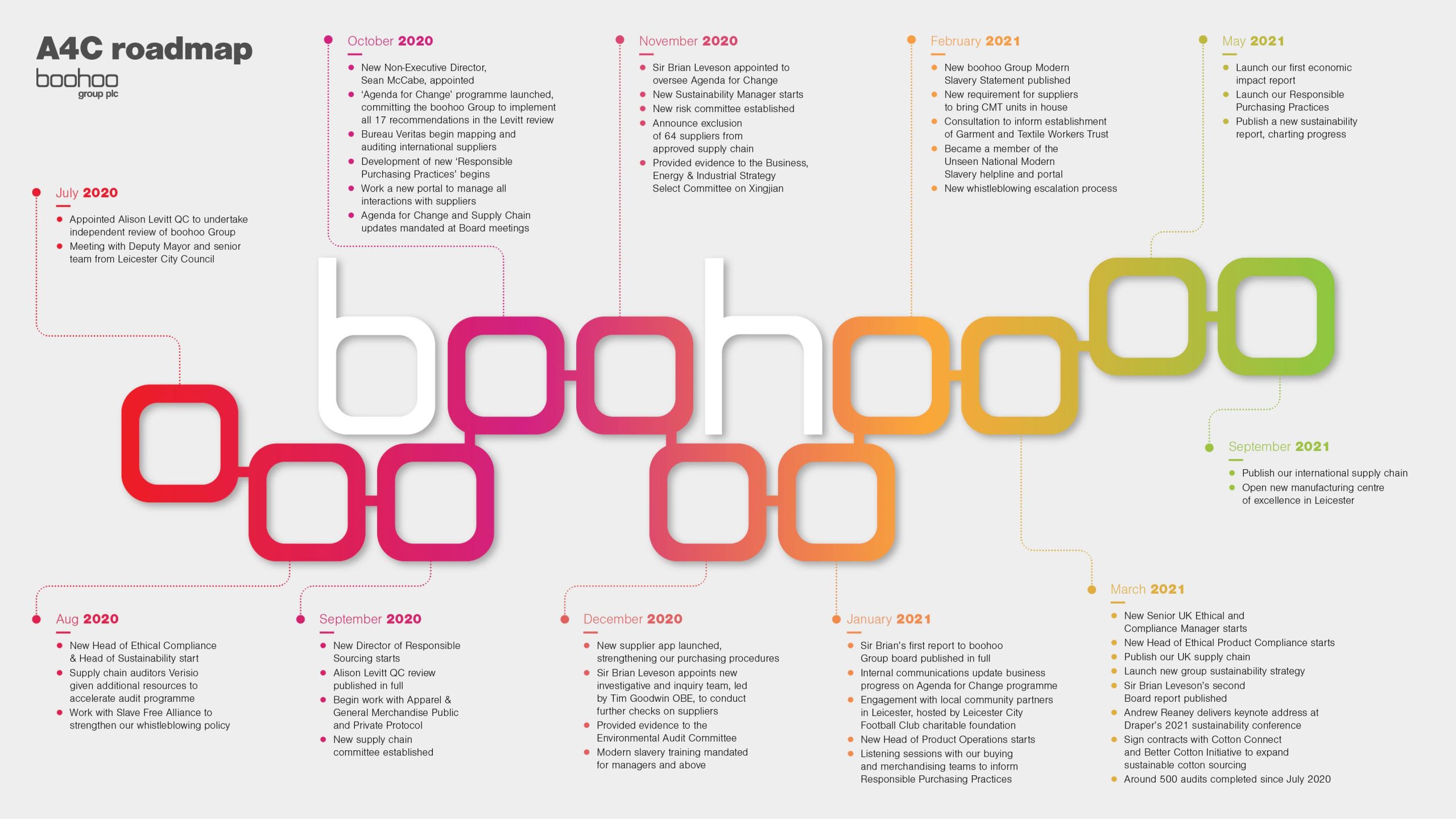

The following November, Boohoo Group Plc appointed Sir Brian Leveson to independently oversee its Agenda for Change programme, which implements the recommendations of Levitt’s report. The Group have focused on six key areas identified in the Levitt Review - "improving corporate governance, redefining purchasing practices, raising supply chain standards, supporting Leicester workers and their rights, backing suppliers and showing best practice in action", according to the company. Boohoo Group Plc's website says: "Everyone in the Boohoo family is determined to ensure that we live up to the expectations of our customers, our shareholders and the general public in delivering on our commitments."

Boohoo's Agenda for Change roadmap set to be completed by September 2021 - Credit: boohooplc.com

Boohoo's Agenda for Change roadmap set to be completed by September 2021 - Credit: boohooplc.com

Boohoo Group Plc representatives attended the Fixing Fashion inquiry, including Boohoo co-founder and executive chairman, Mahmud Kamani, Andrew Reaney, Responsible Sourcing and Product Operations Director and Kelly Byrne, Commercial Director of NastyGal. Mr Reaney set out the route ahead from Boohoo in tackling the issues set out in the Levitt report.

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

But Mr Kamani stated some clear views about the possibility of taking Boohoo's production overseas.

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

Video courtesy of House of Commons Fixing Fashion inquiry (December 2020)

On the whole, Mr Kamani's responses at the enquiry were "very poor" according to Senior Specialist for the Environmental Audit Committee, Nicholas Davies.

Boohoo recognised that changing their supply chain will not be easy to do single-handledy. Mr Reaney addresses the fact that in order to make a real change to Leicester's garment district help is required from all garment factories.

Conflictingly, Mr Kamani attempted to distance the Boohoo Group from Leicester garment factories saying: "We recognise in this industry when we are dealing with an independent factory who is not owned by us, that some of them do not play with a straight bat, as it were."

However, Mr Davies spoke about the impact of such a statement.

Mr Davies continued, saying that the steps being taken by Boohoo to improve its supply chain will be closely monitored by the Committee. He said: "It would be good to see them become fully transparent."

One of the most recent developments in the Boohoo case is the Modern Slavery statement the company issued in February 2021. The statement says: "One of the key commitments we have made as part of our Agenda for Change is to set up a Trust in Leicester which will be overseen and managed by an independent Board of Trustees. We will invest £1 million in this Trust and are currently recruiting for Trustees."

The Trust is said to be for all garment workers in the Leicester Community. It will provide access to grants and crisis funds for those in need and will champion workers’ rights across the sector - a step in the right direction.

As of 19th May 2021 Boohoo has linked a £150 million bonus scheme for its top managers to the improvement of conditions in factories. The company said that their board would have the power to reduce the pay out to 15 key managers, including Mahmud Kamani, if the group’s Agenda for Change programme was not implemented in full.

Academic views

An academic report into Leicester's modern garment industry confirmed low wages and poor conditions

A report conducted by the University of Leicester found that the majority of garment workers in the city are paid way below the National Minimum Wage, do not have employment contracts, and are subject to intense and arbitrary work practices.

Associate Professor in Work and Employment at the University of Leicester and leader of the report, Dr Nikolas Hammer, said: "I feel the pandemic has kind of segmented the industry: those factories supplying online retailers had lots of orders and that's where the Labour Behind the Label report and the Guardian exposés come from. Coincidentally this also featured Boohoo who had the least robust standards and processes in this regard."

The report, published in 2015, summarised the extensive research conducted within Leicester as a UK sourcing hub.

Dr Hammer raised his concerns about the matter today. He said that the numerous initiatives being implemented to help mitigate and eradicate the problem in Leicester specifically are geared to reducing brands' risk (e.g. they work with fewer factories as Boohoo has recently announced). Dr Hammer thinks a different strategy would be better received. "I'd say giving workers and unions access to factories and establishing a broader dialogue would work more effectively."

It is clear that change is multi-faceted - there is no silver bullet. Yet one thing remains simple - change is evidently being urged to help garment workers and the industry as a whole.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to everyone who helped me in the making of this online project. Thank you to those who shared their personal stories and to those who shared the incredible work they were doing.

A special thank you to my father - someone who supported my idea from the very start and drove me around Leicester to take photos for this piece.

Credits:

Produced and created by Amber Sunner

A big thank you to all of the contributors:

Amina*

Saja Elmishri

Meg Lewis

Mark Mizzen

Rob Johnston

Priya Thamotheran

Councillor Adam Clarke

Orsola de Castro

Owen Espley

Fiona Gooch

Nicholas Davies

Dr Nikolas Hammer

Photography

Amber Sunner