NASSER TEYMOURPOUR

How an artist blends Kurdish heritage and conceptual art

Nasser Teymourpour is an Iranian conceptual artist who has displayed his work around the world, from London's Fitzrovia Gallery, to the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

His art style mixes his Kurdish heritage and culture with a very brutalist view of human nature.

He is firm with his conceptual stance and outlook of his work, yet is malleable with his influences.

Nasser has always been confident with his artwork, never faltering from his vision or shying away from controversial topics.

His website is the perfect example of that, featuring art from his whole career. From 'Mefega', a sculpture of a tribute to two young Kurds who were killed in an avalanche. To 'Happening Birthday', a celebration for one of the characters in his rendition of Anton Chekov's Three Sisters, going against the standard flow of the play.

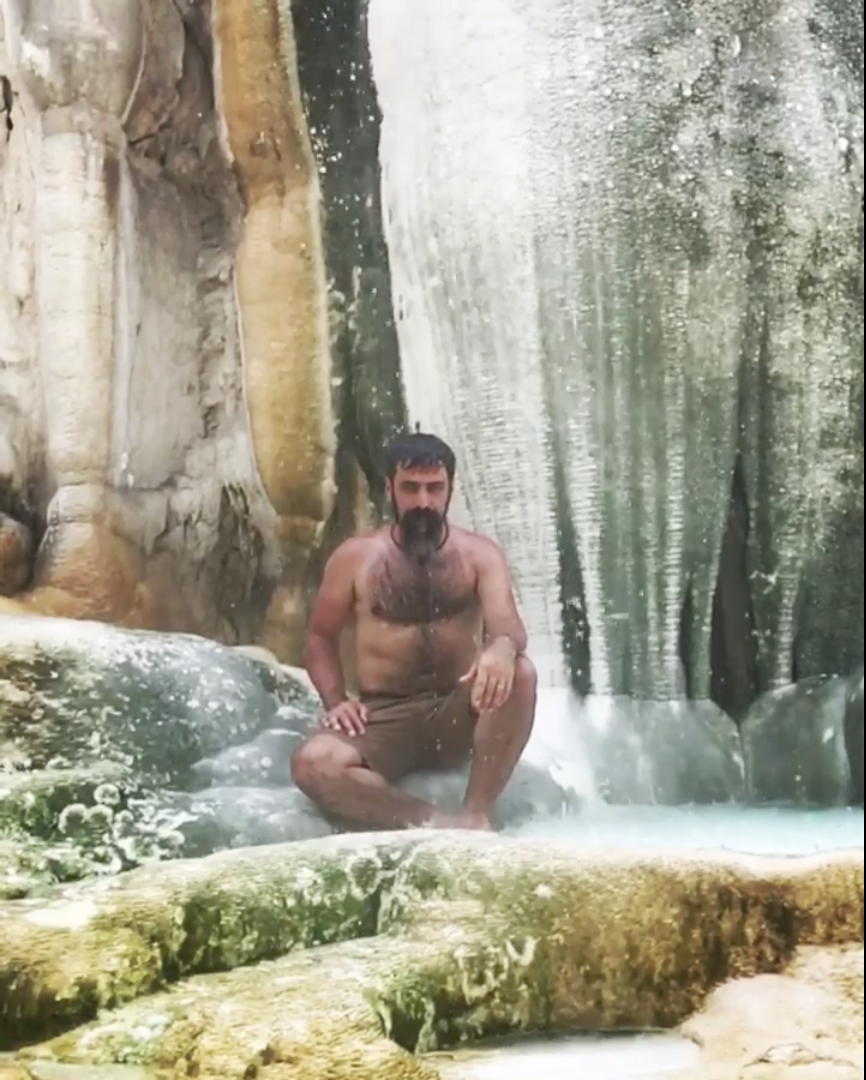

His Instagram feed is very much like any other, but with far more care into the photos themselves.

Most of his images are perfectly framed and lit with magnificent colours. All from his iPhone.

Some of the pictures also include his German shepherd, Shahoo, in his wonderfully rustic and ornate house.

In the more uncertain times of quarantine, Nasser has been creating new pieces of art on a near daily basis.

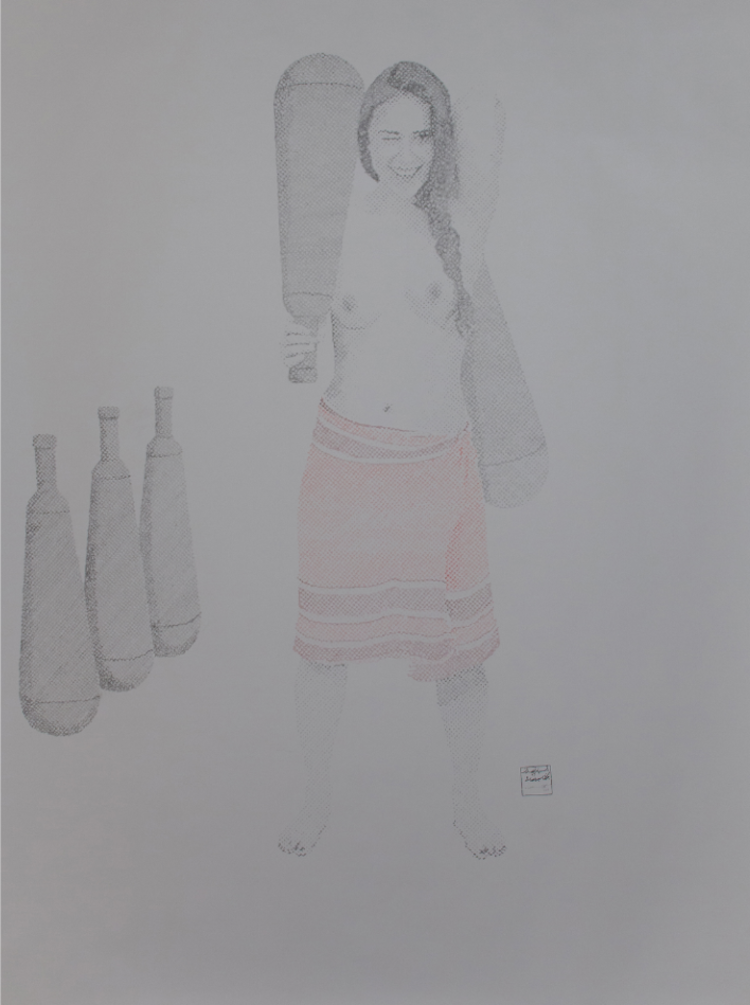

The pieces, which are certainly very provocative, show Nasser turning to figurative art, a constant evolution of his artwork.

The very delicate lines of the drawing brings it to life and gives it a strong, structured tone.

Among the other creations, a similar pattern emerges with the mix of the female form and a collection of different animals, including an iguana, a rhino and a rooster.

He even created his first self-portrait during lockdown.

Political Pop.

Political Pop.

Even his studio is an embodiment of his work. It's flooded with his own work, yet he manages to create an elaborate view of his past accomplishments.

From the floor to the ceiling, there are works of art. Old. New. Big. Small.

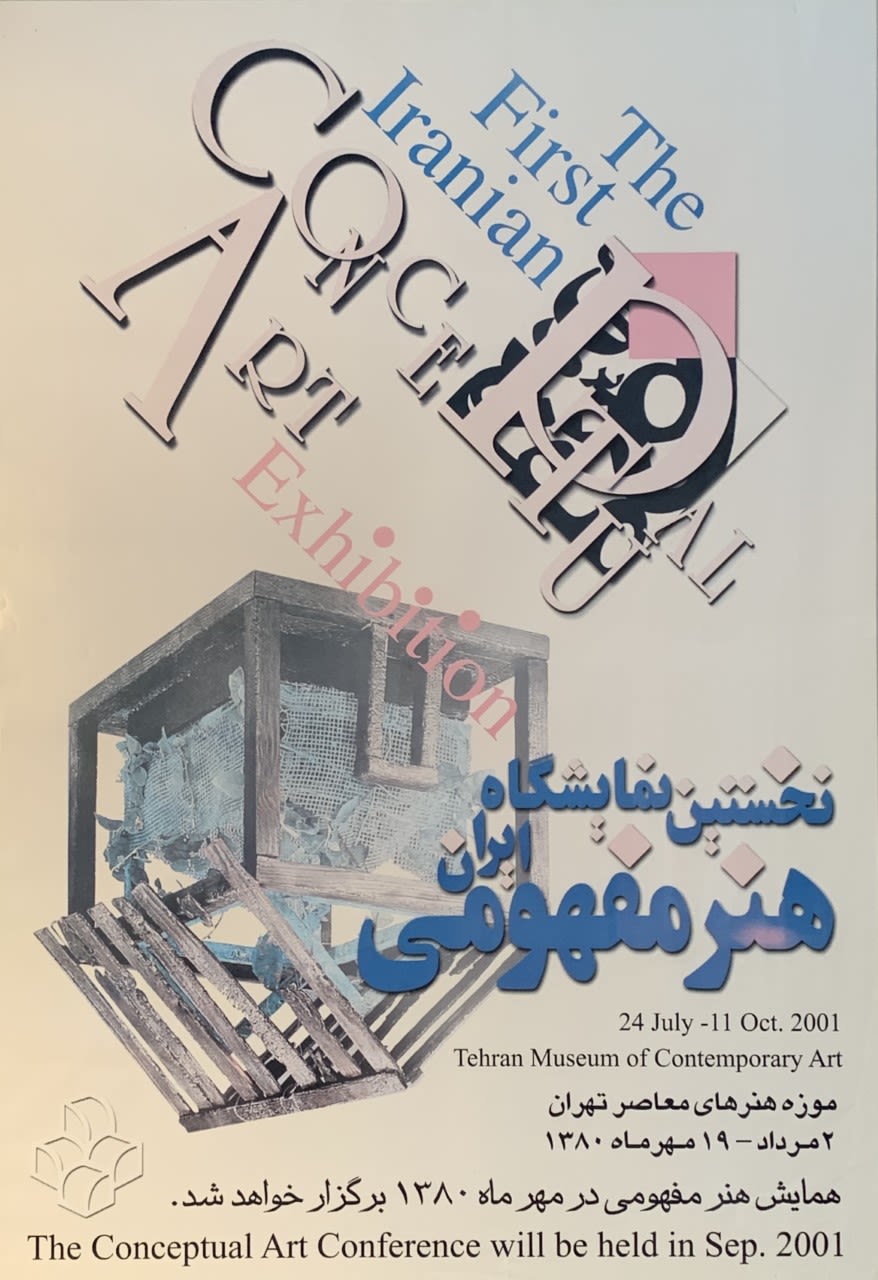

One of his biggest pieces in the room was hung up near the door. It was a very special poster from 2001.

History in the making.

History in the making.

Nasser, along with a few other Iranian artists, held the first ever conceptual art exhibition in Iran. It was exhibited at the world famous TMoCA - Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art - in 2001. It was such a success that he was also involved in the second the following year.

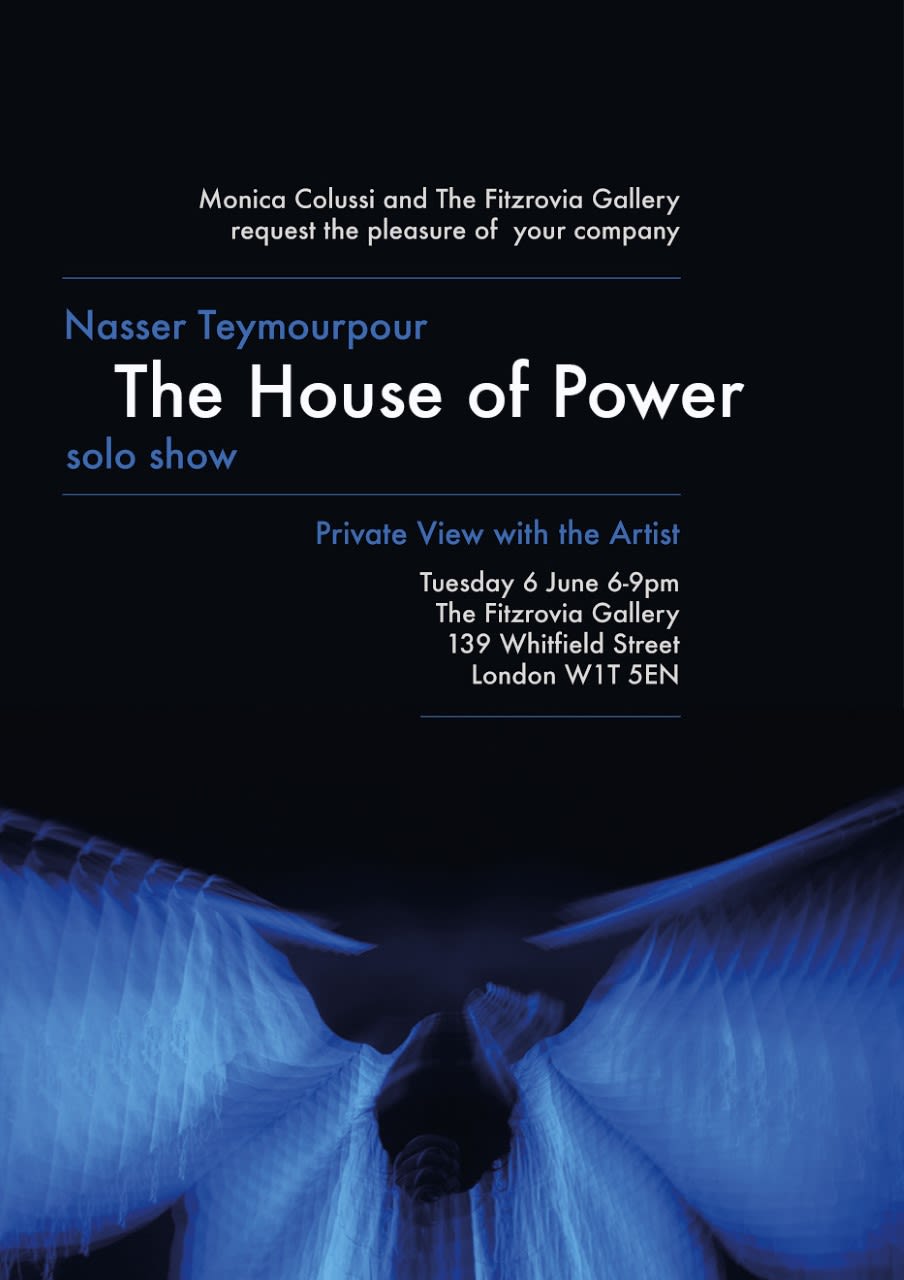

His first piece of featured work at the Fitzrovia Gallery was entitled "The House of Power" and was exhibited in the summer of 2017.

Nasser's first exhibition at the Fitzrovia.

Nasser's first exhibition at the Fitzrovia.

The Fitzrovia website described the work as:

Teymourpour takes a step away from using excessive materials, and focuses on working with a more stripped down palette incorporating his own bodily substances including hair, skin, blood and various others as mediums in his art.

One of the dominating topics of the installation was to give people the chance to do something which would go against the norms. This had a strong emphasis on his work, especially his work of Zourkhaneh.

Zourkhaneh is an old Iranian practice of training men for battle. It translates to "house of strength" and is a sort of traditional gymnasium in which would-be warriors trained to become unbeatable.

For all intents and purposes, this was strictly a man's activity. But, the goal of this exhibition was to give a voice to the voiceless. So, Nasser made the centrepiece of the exhibition as women engaging in traditional practices designed for men.

A naked woman holding two 'meels', which were designed to build muscle by swinging them around. A woman would not have typically used these, showing the breaking down of the gender norms.

A naked woman holding two 'meels', which were designed to build muscle by swinging them around. A woman would not have typically used these, showing the breaking down of the gender norms.

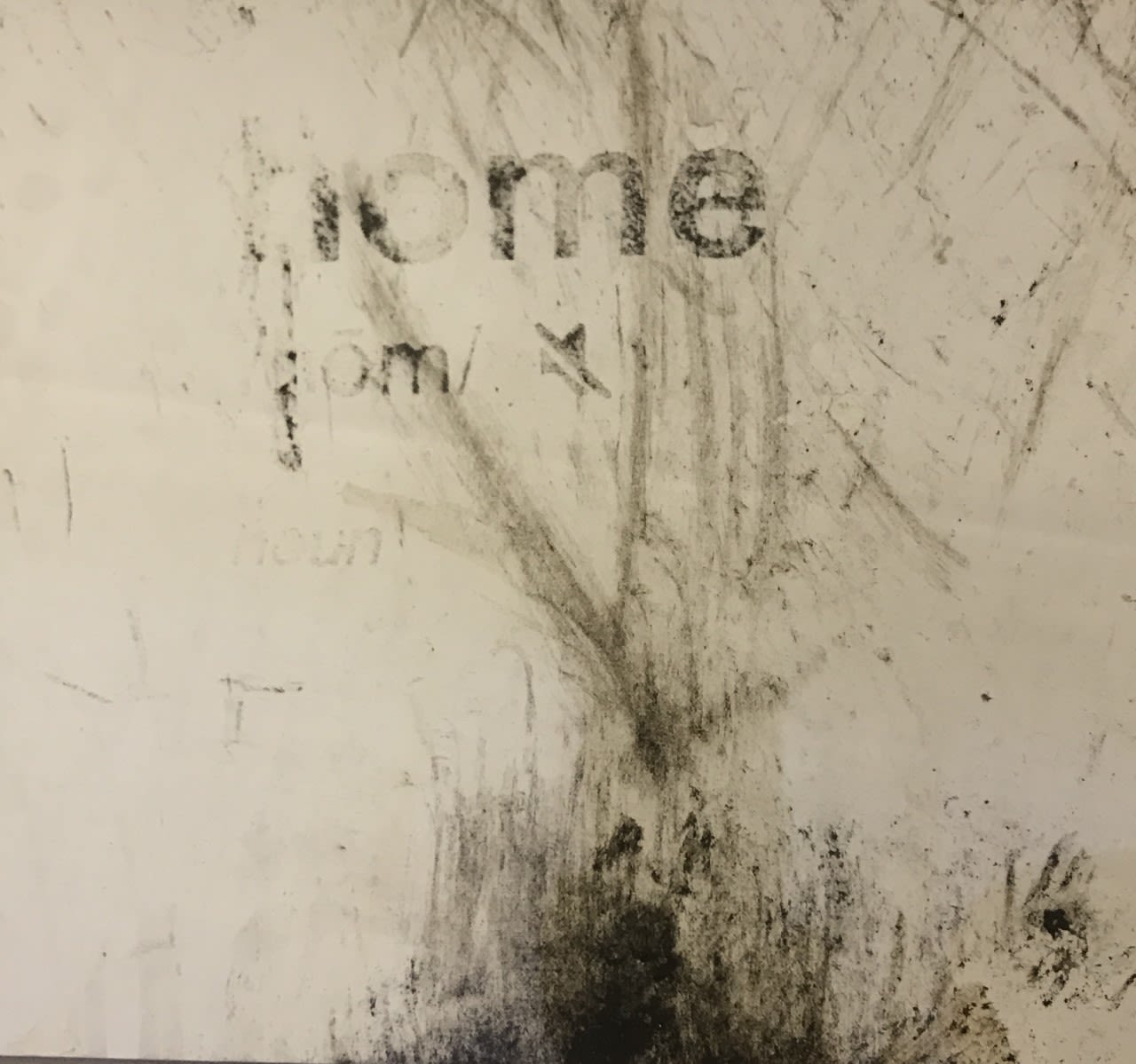

Nasser has also been experimenting more frequently with using spray mount adhesive on cardboard. He sent a few of the boards to the migrant camp in Calais and waited for the results. The final product was a smeared canvas with the remnants of dirt from the camp, exposing the definition of 'home'.

However, that was the only one that was sent back. It was returned back to London on the day of the evacuation of the Calais jungle in 2016.

Home.

Home.

Another of the most striking pieces at this exhibition was a project with a humanitarian twist. During the Siege of Kobani in Syria, Nasser embarked on a hunger strike in solidarity with the fighters, civilians and the land. It was also to take a stand against the oppression of Kurds by ISIS during that time. He continued the hunger strike for a week and using his urine, created an image.

Due to the lack of food, his urine had changed colour and using those different tones, he created art. He wrote of his disgust for extremism in both and Persian and English.

It has since faded, but still holds an incredibly important message, not only with its words, but also with its backstory.

Tucked away in a side road nearby the Warren Street underground station lies the Fitzrovia Gallery. The small, unassuming room has hosted some of the most unique artists in the past and their most recent exhibition is no different.

His most recent exhibition was "The Mountain (ar) Range" with Vooria Aria, another graduate of the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

The exhibition stems from the Kurdish proverb "kurdek hevalek tune lê çiyayan" or "A Kurd has no friends but the mountains". The idea of the name is a reference to Kurdish culture and heritage as the topography and geography of the Kurdish region is very mountainous, thus lending itself to the traditional way of life. This was also the title of Behrouz Boochani's award-winning account of his detention at an Australian immigration facility on Manus Island from 2013 until 2017.

From the outside the work has a simple outlook, three podiums spread out across the room. But that is wrong.

When you step inside, you get hit with the sounds of the Iranian protests over the last month. The noises of men, women and children crying, various shots being fired. It reminds you that all of this is still happening and the art doesn't let you forget that.

Both Nasser and Vooria collected sounds and videos that had been uploaded by Iranians that had been caught up in the protests and subsequent repression by the government.

The haunting screams and shrieks of injured protesters and civilians' rings through as you observe what they have created to portray their message.

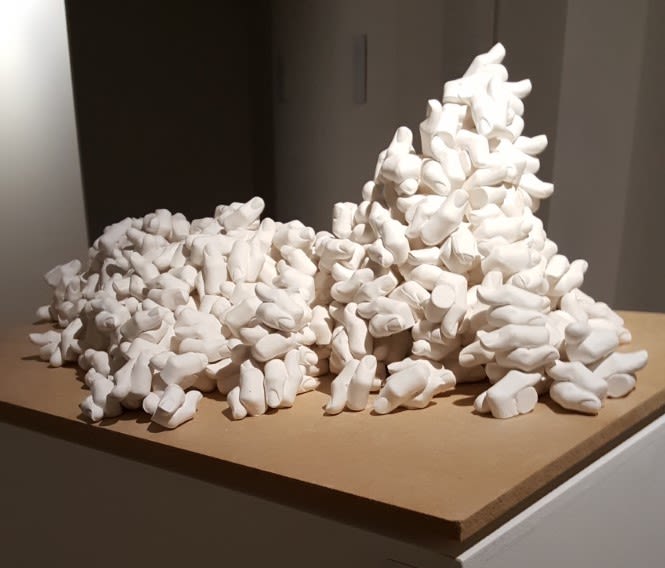

A mountain range made of sunflower seed shells that had been hand-cracked.

A mountain range made of sunflower seed shells that had been hand-cracked.

A mountain range representing the norms of general society. The sunflower seeds are the common snack for the people who let the conflict pass them by, a statement on the people that do not care for their country's hardships and internal struggle.

The unintended damage done to the front right corner of the structure shows the fragility of the nation. Despite the fact that they are deliberately not getting involved, they are still affected and prone to breaking.

The tape around the piece (which was laid down after the initial break) gives an inadvertent meaning as the people are cut off from the rest of the exhibition as they are not bothered by what is happening in the further pieces.

The second pillar, another mountain range made up of pinky fingers. It has many different meanings depending on what culture you are from.

A mountain range made up of pinky fingers made of clay.

A mountain range made up of pinky fingers made of clay.

In Britain, it was seen as a form of being upper class to drink with your pinky extended, albeit a very old fashioned way. In Iran, linking little fingers reinforces friendships.

In parts of Kurdish folkloric dances, men and women stand alternately and shoulder to shoulder and dance while having their little fingers joint to form a chain symbolising unity.

Such a tradition is usually seen at weddings, and could be seen to be done in memory of those who died in a suspected IS attack on a Kurdish celebration in Gaziantep in 2016.

The third and final pillar was the biggest of them all. It may look like a giant wooden box, but it is far more than that. It is power and authority. It towers over everything else and is held up by the smallest of dominoes.

The domino effect.

The domino effect.

The precarious foundations of the structure is reminiscent of actual government, often being maintained by the smallest of supports. Whilst still an imposing structure, any shift in movement and the whole establishment comes crumbling down.

The intense darkness behind the final model makes the grandiose column even more imposing. It towers over everything in the gallery and has an ever-present feel no matter where you are.

As you turn the corner past the final pillar, you again hear the cries of the protesters, chanting against their government and making their voices heard.

The small speaker amplifies the sounds of the protesters around the room to make you reflect on the installations you have just seen. It makes them seem even more remarkable.

The absence of light allows you to only focus on the noise of the protesters, only highlighting their plight even further.

But this could have been a very different exhibition.

Both Nasser and Vooria changed their minds following the Turkish bombardment of Syria in October 2019. They decided that it was about more than just their own heritages and was a global issue.

"What happened in Northern Syria is something above nationalities."

"What happened in Northern Syria is something above nationalities."

Currently, Vooria is trying to get the same exhibition to be held in Vienna, his home. It would remain as a joint project between the two of them, but could have a different message, given the changes they made before the final showing of this exhibition.

Outside Influences

From Pollock to demons

Nasser cites some of his biggest artistic influences as Marcel Duchamp and Jackson Pollock.

They both have influenced his work massively as two contrasting examples of work, Pollock with paintings and Duchamp with sculptures.

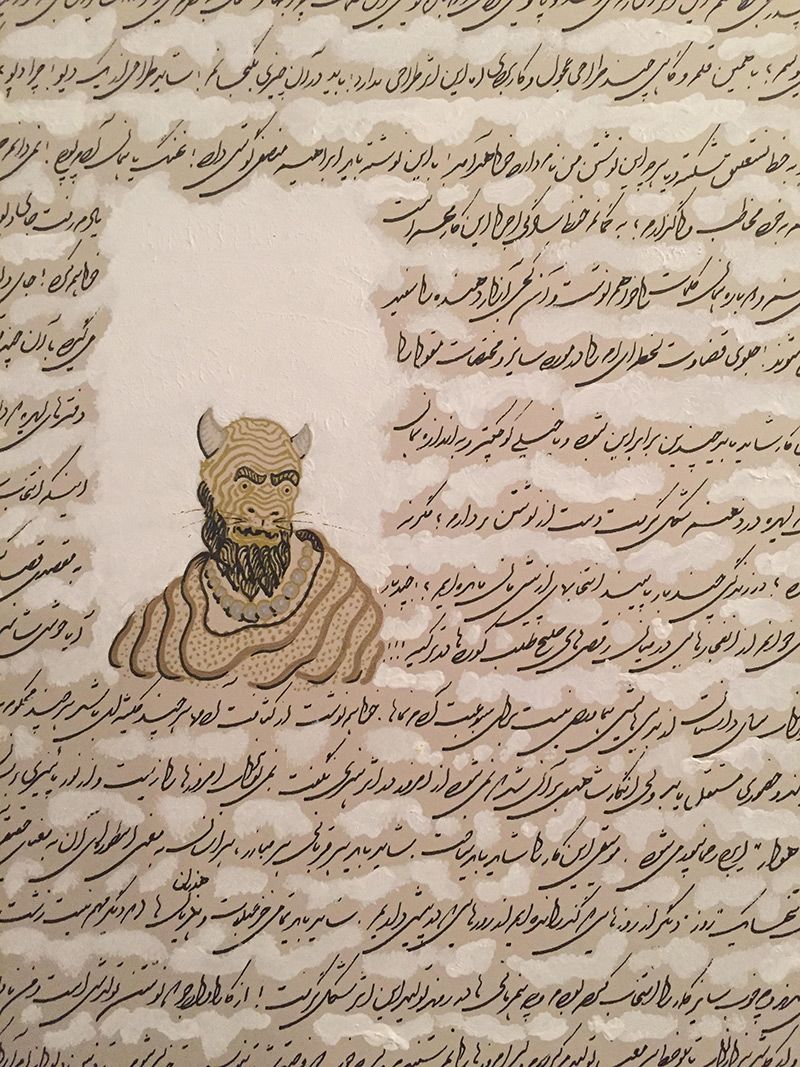

Yet, he has one profound inspiration that continually comes up in his work. Demons.

Nasser has created many images of demons. Like this one to the left and many others below. They all seem to stem from his interest in mythology and the simplicity in something so fractured.

When explaining why he drew demons so often, he said this:

"This piece does not have a sketch. I must include something. Maybe a sketch of a demon. Why a demon? Who knows. I like demons. I like drawing demons in its basic form. The demon's root! A head, an eye and a horn. I assume I should draw it with a golden pinball, in the bottom third of the frame on the left."

Not all of his influences come from famous artists or ancient Persian mythology. There is very little that does not inspire the 39-year-old artist.

The influence of Kurdish heritage isn't just present in Nasser's artwork, but can be seen throughout the wider world. It has no limits to culture, art, sport and a number of other characteristics.

The map shows the far-reaching nature of the Kurdish influence. Whilst those in the Middle East are still struggling for an independent Kurdistan, Kurds have become a universal nationality.

In the future, it is still to be seen what Nasser's next step will be. But he has one main aim.

ANARCHY

He acknowledges the steps he has to take to continue as an artist in a constantly evolving culture.

The idea of anarchy thats is being portrayed throught the art is that of a constant revolution of ideas and to create uncertainty amongst former norms.

We should try to find our own natural order instead of following and accepting the authorities.

The process.

The process.

The video shows one of his most unique projects, with an excellent backstory. For days and weeks at a time, Nasser sat in silence and near darkness to paint this piece, listening only to traditional music. Despite not being particularly religious, he took inspiration from traditionally faith-based music and poems, which helped him create this piece.

So, what are his goals? How does he want to carry his art forward into the future? Is he interested in creating a vision for the world? Does he want to exhibit his art at MoMA? Or the Tate?

Changing attitudes in art.

Changing attitudes in art.