'I couldn't wait any longer'

Johanna Chirinos

Johanna Chirinos left to look for a better life, a life that she wasn't willing to wait for in Venezuela.

"I'm 30 years old, at what age was I going to have my (own) stuff and (start) my family?", she says quite emphatically, "When I'm 50? That's impossible".

There was no future for her in Venezuela.

She had recently graduated from university and could only get minor jobs with her degree.

Without enough money to live on and with the constant threat of crime and shortages in the country, Johanna decided to leave Venezuela.

In the end, she could only wait so long.

"I emigrated because of the lack of public safety".

"I emigrated because of the lack of public safety".

Johanna completed her Civil Engineering degree one year before coming to Peru. It was 2017.

She had started working as an assistant engineer in a building project in Caracas, her home city. She was only starting her professional career; however, the salary wasn’t enough for her to live on it.

With inflation in Venezuela at more than 1,000,000%, the currency has devaluated tremendously making it almost extremely difficult to acquire goods or pay bills.

Johanna had been planning to leave for a couple of months. Caracas wasn’t safe with murder and crime rates on the rise; there were shortages of all goods and there were no high-paying job prospects in the country. It just wasn't the place to begin your career.

She was looking to settle in Argentina and had prepared all of her documents for that destination, but, from one day to the other, things fell through. Then, Peru emerged as an option and her cousin, who had been living there for more than one year, had been constantly begging her to move to Lima.

“She (her cousin) kept telling me ‘come you’ll be better off here, here you will be able to support your family, you’ll be able to be more at peace”.

Peru made sense to her. The work prospects weren’t bad, and the government was facilitating temporary working permits (PTPs) for all Venezuelans. She didn’t think it twice and two weeks later, she had plane tickets to Lima.

“You have no idea”, she says quite emotional, “I felt so nostalgic when I left my parents and my sister at the airport”.

With tears in her eyes, Johanna began her personal journey to Lima.

Johanna didn’t experience the rough journey that some Venezuelans go through to get to Peru. And although, her family had enough money to buy her a plane ticket for half of the journey, she still recalls it as an arduous trip.

“The trip was really hard. I travelled from Caracas to Merida (closest airport to the border) in a plane and then in a car all the way to the border with Colombia.

"From Cucuta (border city) to Bogota I took a bus and believe me I suffered a lot in that trip. I can’t imagine how much have they suffered: those people that came walking”.

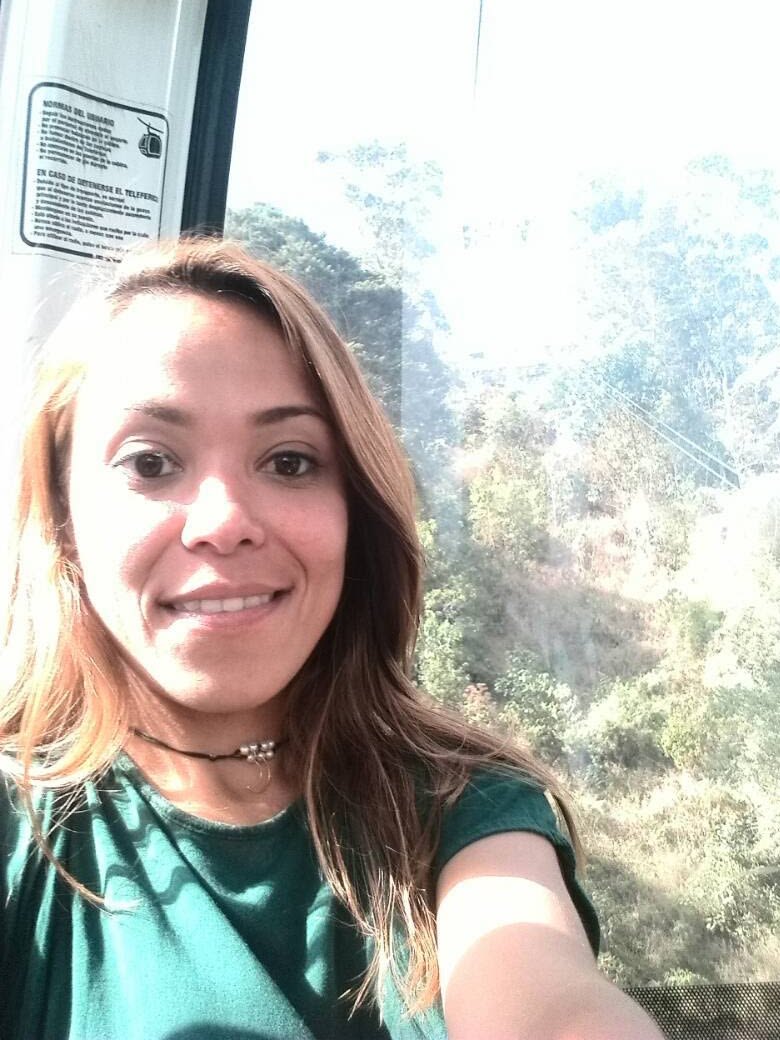

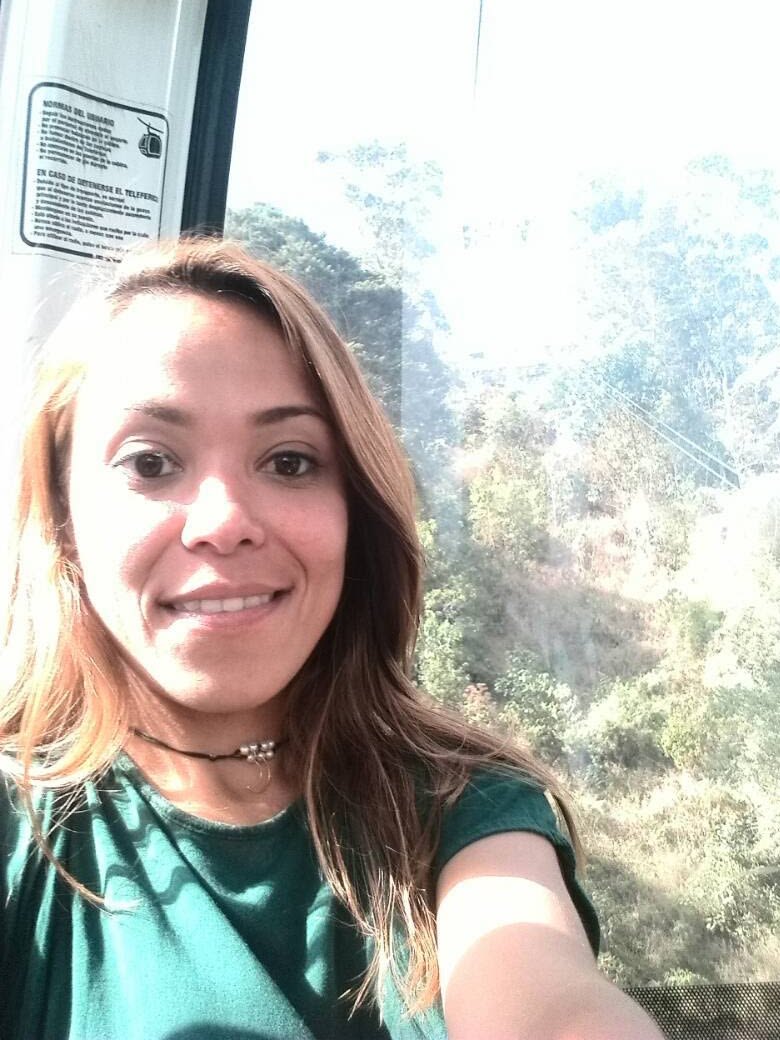

Johanna at the cable car in Caracas (2018)

After a couple of days travelling, Johanna arrived in Lima on the 5th of June. Her first week in the city, however, was something to forget about.

Johanna had heard a rumour that said that most Peruvian men were harassers and so was afraid to leave her room during her first week in the city. They idea of leaving her room made her panic.

Johanna at the cable car in Caracas (2018)

Johanna at the cable car in Caracas (2018)

Johanna at a park in Lima (2018)

Johanna at a park in Lima (2018)

Eventually, she disregarded the rumour and left her room to begin to look for a job, however, it proved to be harder than what she imagined.

For more than one month, she looked for work without much success. She hadn’t validated her degree yet so couldn’t practice engineering in the country. She didn’t know what job to get but was sure which one she didn’t want to do.

“I said to myself ‘I don’t know how to be a waitress, I’m afraid that on my first day all the dishes are going to fall and it’s going to be a complete disaster”.

Johanna at a park in Lima (2018)

Despite all of that, Johanna managed to land her first job in Peru in a networking company. It was a different occupation from the one she was used to have but was happy to have secured something.

Her boss was really understanding and a supporter of the fleeing Venezuelans. He made her transition into the new job a lot easier.

Not long after landing her first job, she would get a weekend job as a hostess in a restaurant.

After a couple of months, Johanna had adapted to the city and thanks to her cousin, she was already going out and making friends.

“I have been lucky and I’m doing well. I feel comfortable but I’m still trying to steady the ship (her life).”

However, there’s always something in her chest, a feeling, that she can’t seem to shake.

“No matter how comfortable you are, how good you can feel, there’s always something in my chest that doesn’t go away”.

Johanna misses her family.

“It’s a feeling that doesn’t go away. It’s just seeing them (her family) in a camera and (I) feel that they are far away and there’s nothing I can do about it, just send them hugs and kisses and tell them ‘it’s all going to be okay’.

“Sometimes I feel sad and I want to go back to Venezuela and hug my mom and for all of this to be over. Still, I always encourage and say to myself ‘you have to keep fighting for them, for you, for everything”.

Johanna with her family in 2017.

Johanna with her family in 2017.

Johanna will never stop missing her loved ones, however, her life now lies in Peru and she doesn’t think about going back for good.

“I would like to go back to Venezuela but only to visit”, she says adamantly, “to visit my mom”. She misses home but is now comfortable in Peru.

She plans to validate her Civil Engineering degree in her new country to work in what she truly loves, “it’s one of my main objectives”, and to continue to balance her new life.

Johanna walking through Lima (2018)

Johanna walking through Lima (2018)

And yet, the crisis is still on the back of her head. But no matter how dire the situation, Johanna feels that all Venezuelans can learn something from the crisis.

“I feel like this has taught us to value the millions of things that we had and that we didn’t value. It makes me nostalgic just to think about it”.