Chasing the win

The hidden cost of sports gambling

They come from different walks of life. Two are ordinary citizens. One is a former professional footballer.

Simon Haworth, Neil Kerr and David Quinti are three of an estimated 138,000 people in the UK living with a gambling addiction.

In a country of nearly 70 million, their stories are easy to overlook. But it’s exactly because they’re so unexceptional on the surface that their experiences matter.

Each has faced the trials and tribulations of a gambling addiction.

For one, it was entwined in the culture of a professional sport. For another, it was a way to cure boredom that spiralled out of control. For a third, it began as weekend bets that ended in financial ruin.

All three faced the consequences—mental health crises, broken relationships, shame—and they all found a way to come back.

I sat down with them to understand not just what addiction took from them, but what it left behind. Their voices are striking not because they are rare, but because they are so familiar.

In sport, gambling is ubiquitous—it is the sponsor on your team's shirt, their logo is plastered around stadiums, their ads are shown at prime time in between breaks of action, and the biggest names in the world are their ambassadors.

The stories of these three men are distinct yet remarkably similar. While they differed on the amount of money they lost, they lost something even more important.

Themselves.

They all heard the slogan, ‘When the fun stops, stop,’ but when the thrill takes hold, nobody can stop.

Simon Haworth

"My gambling started as a young boy. I was born and raised on a council estate in Cardiff. My Grandad liked to bet most days, and I started picking out horses for him at the age of five or six.

"Then at the age of nine and ten, me and my friend would use our pocket money to pick out a few horses and his dad would put the bet on for us.

"We were around people who bet lots. It became part of our culture."

Simon Haworth was a professional footballer who played in the Premier League for Coventry City and earned five caps for Wales after making his international debut in 1997, before a knee injury forced his premature retirement in his late twenties.

“I always enjoyed the horse racing. The bets started to progress when I became an apprentice footballer at Cardiff City. I would put on bets for the senior players on a Saturday, and that fed into the culture and boosted my ego.

"I was on £27.50 a week, and if I won bets for the older players, I could get £40 or £50 off them.

"The buzz became real.”

Whilst he was still playing football, the gambling was “never a problem.” Simon got into the business of owning racehorses, and his bets were safe, not rambunctious.

His interest in horse racing was genuine; it was not just a gambling interest.

But then in 2005, Simon was forced to retire after breaking his tibia and fibula.

He thought that with the money behind him, he would “cruise through life.” Looking back, he said that he was so “naive.”

“Gambling then became a problem. There was a lack of purpose in my life. I was trying to fix the pain in my life.

Simon talking about the pain of gambling

Simon talking about the pain of gambling

"I struggled to transition into the ‘real world, ’ and gambling gave me that feeling. I was also under pressure to keep up my financial lifestyle.

"I was married and had two boys in private school. Gambling became my coping mechanism.”

In a study conducted by the Professional Players Federation, gambling addiction in professional footballers is three times higher compared to young men.

Simon is just one of many ex-professional footballers who developed an addiction. Players such as Keith Gillespie and Paul Merson have been public about their gambling problems.

“I was in denial about my addiction. You can go from pretty regular to disordered quickly because it is a silent addiction. I did not want to look inside myself because I was an addict.

"It was not long before I ran out of money. I managed to keep my house, but I got divorced from my wife. "

"My mental health became really bad. I was thinking things I shouldn’t have been.”

Gambling truly is a silent addiction. With alcohol or drug abuse, you tend to be able to see it on the person. With gambling, the person can look fine from the outside. In 2023, Gambling with Lives estimated that 409 people committed suicide each year due to their addiction.

“Gambling had the biggest effect on me emotionally. I lost myself and relationships with people close to me.”

Simon at his boyhood club of Cardiff City, delivering a gambling awareness talk (courtesy of Simon Haworth)

Simon at his boyhood club of Cardiff City, delivering a gambling awareness talk (courtesy of Simon Haworth)

Then, with nowhere else to turn, Simon contacted the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) union to seek help.

He became committed to facing his addiction. With the PFA, therapy and Gamblers Anonymous, he was able to quit.

Simon has said, “I wish I had listened to myself earlier. There were many moments I knew I should have reached out and been accountable, but I didn’t.

"It is never about the amount of money. It is who you become as a human. You become a liar, a cheat, and a deceiver of people. That is the real dark side of problematic gambling.

"I wish I was honest enough with myself to go and speak to people. I am sure if I had done it, I could have got the help I needed.”

Simon now works as a senior consultant at IC360. Prior to this, he was a lived experience facilitator at EPIC Risk Management. He helps pro sports players understand the risk of gambling and the dangers it poses.

He said he would like to see clubs integrate gambling awareness and mental health as part of a weekly programme. He wants players to become more “educated” and have support when they leave the game.

“Mental health needs to be part of the programme. There is a lack of a therapeutic approach. We need to take a step back and see how people are mentally.

"On a societal level, gambling is a massive issue. So much more needs to be done. It affects so many lives because of how accessible it is. It is far easier for people to gamble now.”

Simon conducting a gambling talk with the Newcastle Falcons Rugby Club (courtesy of Simon Haworth)

Simon conducting a gambling talk with the Newcastle Falcons Rugby Club (courtesy of Simon Haworth)

Neil Kerr

“I grew up in a small mining village in Scotland. There was not much to do in a small town as a teenager.

"You could have a kick about, but that was as far as it went. Then one day, I saw a crowd of older boys in a circle.

"And when I peered over them, I saw a huge pile of money. From this point on, I was attracted to money.

"Not so much what it could get you—just the pure appeal of it. Me and my friends started playing for pennies under street lamps. I was hooked from this point.”

Neil as a child (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

Neil as a child (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

This is Neil’s story. A man who was addicted to gambling for 25 years. During these 25 years, he moved through dozens of homeless shelters, lost thousands of pounds, and spent time in prison.

He is just one of millions whose lives have been affected by gambling.

“I knew I could have a system. I was held back in school. I had special classes at primary school.

"If they had asked me what six 70ps’ s were, I’d know that would be £4.20. But I didn’t know what 6 x 7 was.

"Looking back in hindsight, I can see that my home life was not comfortable. My father left when I was seven.

"My attention wasn’t on school. It was on gambling.

"And as my gambling addiction got worse, I masked my emotions through alcohol and magic mushrooms.”

Neil isn’t the only person who started gambling young. A survey by the Gambling Commission in 2023 found that 85,000 individuals aged 11–17 had gambled at least once. That translates to 1.7%.

With gambling becoming more accessible, this number will likely rise.

Children watching sport on TV are bombarded with gambling promotions—on team kits, in adverts, and plastered around stadiums.

It draws them in. And once it hooks them, it rarely lets go.

Neil’s life spiralled further out of control as an adult. After being placed in institutions due to drug addiction, he lived like a hermit.

“Me and two of my friends broke into a workplace and stole some things. We got £500 in cash and made our way down to London."

"If I didn’t know any better, I’d have thought that’s where they got Trainspotting from.”

It didn’t take long for the three to be caught by police.

Neil was sent to prison on remand. He was just 21.

A 2023 government report showed that 3,744 people in UK prisons had a serious gambling problem. With 95,526 people incarcerated that year, just under 4% were problem gamblers.

Even more concerning: 20,658 people across the UK became alcohol dependent due to gambling, yet only 12% received treatment.

Gambling leads to other addictions. Neil was addicted to alcohol and drugs—like so many others.

“I ended up in a homeless shelter just a few miles from my house. I went to a gambling counsellor.

"But as soon as that cash touched my skin, my mind shifted to the races. I knew all of them in my head.”

That wouldn't be Neil’s last homeless hostel. He moved between shelters across England and Scotland, battling his addiction.

He couldn’t build meaningful relationships. He lost his family. His only friends were others in the hostels—people also struggling with addiction.

He attended Gamblers Anonymous and quit for a few weeks at a time, but the addiction always came back.

And it only got worse.

“Unbeknownst to me, I was drinking as well. I drank to commiserate, and I drank to celebrate.

"Alcohol was my best friend because it took away the pain I had created in my life.

"It was a world of fear and dread.”

Then came a turning point. Lying in bed, cold sweats and coughing blood, Neil made a decision.

Three days later, he stopped drinking.

Neil in his flat in Worthing (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

Neil in his flat in Worthing (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

Soon after, he went to a Gamblers Anonymous meeting. He saw others being recognised for their progress and decided to commit.

Eighteen months later, he had stopped completely. And oddly, he had also stopped swearing.

“I ended up going to college and I got a diploma.”

With new confidence, Neil started his own Gamblers Anonymous group. He supported individuals, group meetings, and even prison inmates.

In 2007, he attended the 50th anniversary of Gamblers Anonymous. He spoke on stage and broke down in tears.

“Standing there in front of 200 people, it took away my fear towards life. Nobody could understand what I said, but it didn’t matter. I came away with even more commitment to stop my addiction.”

After 20 years of gambling, Neil finally found peace. He reconnected with old friends and family.

“I told my mother I loved her for the first time.”

Neil’s last bet was on 16th November 2005, nearly 20 years ago. He is now a completely different man. He’s found love and is writing a book about his life and addiction.

Today, he works as a gambling counsellor at Breakeven. He has his own flat—and, most importantly, he has his life back.

Neil running the Brighton marathon (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

Neil running the Brighton marathon (courtesy of Neil Kerr)

David Quinti

“It all started when I started going to the bookies with my friends when I was younger. We were only betting a few pounds each—it was just a bit of fun, and then we’d go to the pub.

"I didn’t think there was an issue with it at the time.

"It was nice to get a win—it would help with the night out. It felt like free money.”

This is how it begins for many people. What starts as a harmless bet can quickly become dangerous. There’s no shame in placing a £5 bet on a football match for fun. But when it progresses, it becomes harmful.

David originally gambled for fun—just a laugh with mates and a bit of extra money when a bet came through.

But it didn’t stay that way.

David began betting more often.

“It was mainly sports betting—football. I followed the leagues, so I thought I had some knowledge. I was enjoying the fun side of it, but it continued.

"I joined lots of online sites—at one point, I was using 16 different operators. It opened a new world. I didn’t have to go out to bet. I started spending more than I should—over £100 a week.”

From there, a dangerous cycle began.

Chasing your losses is a common phrase in the gambling community. When you lose a bet, addicted gamblers double down. Instead of accepting the loss, they increase their stake to win it back.

Sometimes it works. But in most cases, it leads to a spiral—hundreds, sometimes thousands lost in just a few hours.”

“There were other leagues to bet on through the night. I didn’t know anything about them, but I bet on them because they were there.

“I’d start putting silly bets on—like £20 on the next goal scorer. When that didn’t come through, I’d do it again.

"That number just increased. I started to lose £300, £400 quid, and I was desperate to get it back and win more.

"Sometimes I got a big win such as £200. But I would have lost double that throughout the rest of the day.”

And this is where David’s personal and work life took a dramatic turn. He started calling in sick and gambling during his workdays.

“When I was at home, I was on my phone constantly. Nobody knew what was going on. I was hiding it from everyone.”

David talking about the isolation that comes with a gambling addiction

David talking about the isolation that comes with a gambling addiction

Just like Neil, David turned to another substance to help him with his mental health. Alcohol. He started to drink more and more, which, in turn, caused him to gamble more.

A study conducted by Bussu and Detotto shows that 10-20% of problem gamblers also have a drinking problem.

“All I could think about was gambling. I would take loans out, use credit cards, and it just led to me losing more money and my mental health became severely affected.

"I missed time with my kids as I was too busy trying to win money back. I started gambling on roulette because I was desperate.

"One night, I started putting a few hundred on roulette and I lost over £3000.”

Things only got worse for David. He lost around £40,000 from a joint account he shared with his wife. His addiction was damaging his family in ways they didn’t even realise.

He reached a very dark place. The weight of the debt, the strain on his marriage, and the pressure from work all became too much. He began to contemplate suicide.

Thankfully, he didn’t go through with it.

One night, while David was gambling on his phone, his son walked into the room.

“Dad, I wish you would stop doing this.”

David with his son holding the Champions League trophy (courtesy of David Quinti)

David with his son holding the Champions League trophy (courtesy of David Quinti)

That moment hit David hard. It was the turning point. He decided then and there that he had to stop. Two weeks later, he quit gambling.

But his journey was far from over.

He had been building up the courage to tell his wife about the money he had lost. Before he could, she noticed the missing funds and confronted him.

David confessed everything. They separated shortly afterwards.

Determined to get better, David began seeking help and eventually found support through gambling counselling.

“I remember the first counselling session. I was in tears.”

He found it very difficult to reach out. When he went to the doctors, they were more interested in his alcohol addiction.

His counselling finally ended, and not only did his wife take him back, but he also started his career in counselling.

He became the founder and co-leader of the Gambling Lived Experience Network, a charity for people recovering from gambling addiction.

“It felt like therapy to me. I was able to put something back and clear my mind.”

David’s last bet was almost 10 years ago. The road back to normality wasn’t easy, but he made it. Today, he works as a peer aid coordinator at Bet No More and has his family back.

David holding his firstborn (courtesy of David Quinti)

David holding his firstborn (courtesy of David Quinti)

The hidden danger of free bets

In the United Kingdom alone, 48% of adults gamble. This can range from as harmless as putting £2 per week on the national lottery, to splashing thousands every day trying to chase the dopamine of hitting that big win.

Sports gambling alone brings in 8% of this 48% figure.

For most people across the country, sports betting is not a problem. It is a fun way to spend a small amount of money and even possibly make a bit.

But for a select percentage, it is a toxic addiction that shows no sign of stopping.

One particularly damaging aspect is the concept of free bets.

People I spoke to during my research consistently raised concerns about how these offers can serve as a gateway into gambling addiction.

What appears to be a harmless promotion—a free £5 to bet on your favourite team—can quickly become the perfect trap.

A prevalent and sad article was written on this exact matter.

Luke Ashton had a wife, two children, and a home. From the outside, it looked like he had the perfect life. But beneath the surface, he was battling an addiction that would ultimately cost him everything.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, after being furloughed from his job, Luke received a free bet offer from Betfair—despite having opted out of all marketing communications in 2017.

That single offer reawakened his addiction. Just a few months later, Luke took his own life, having accumulated £18,000 in gambling-related debt.

His wife, Annie Ashton, said, "How much worse does it actually have to get before the Gambling Commission switches that switch and investigates? It doesn’t seem like they’re ever likely to."

Annie now campaigns with Gambling with Lives, a charity dedicated to supporting families bereaved by gambling-related suicides and pushing for stricter regulation of the industry.

My interview with an anonymous bookmaker

"I have seen people put a couple of grand on at one time."

From a small town in the United Kingdom, I spoke to a bookmaker who asked to remain anonymous to ensure they did not face any backlash from their employers.

"Like any other business, we get regulars. You tend to get some older people coming in daily and doing a few bets. a £10 here, a £5 there. For a lot of people, it is the social aspect.

"But then there are the other types of regulars. These people do not come in every day, maybe two or three times a week. While they are there, they bet on every single horse race.

"I have one customer who spends £20 on every horse race that is on, but at the same time, he is betting on the virtual horses."

In a study done in 2024 by the Department of Trust, they found that the average high-value gambler spends £191 a month on betting—£150 more than low-value gambler.

This highlights how much more some gamblers spend. £150 can be the difference between paying the bills and getting kicked out for not paying rent.

Coral on Gillingham high street

Coral on Gillingham high street

"20 years ago, I worked at a shop with a bandit screen (robust, protective barriers designed to enhance security at tills in bookmakers). We had a dispute with a customer after he was late putting a virtual bet on.

"So when he went to put a bet on for the second virtual race, I saw that he deposited the money on time, but it still said it was late.

"I rang up head office, but they said they would not pay him the money out."

As my source was writing down a customer number for the man, she heard a massive 'smash' before the sound of glass breaking as it hit the floor.

The customer had his brick phone and was hitting the bandit screen, forcing it to bullseye.

The manager of the shop, along with a customer, bundled the vandal out of the shop before calling the police. But while they were on the phone, he came back with a shovel.

"He smashed the front door and the windows of the shop. We had to leave the shop as it was and run upstairs to the flat above the shop.

It took the police over an hour while we were held upstairs. We found out later that the customer was drunk."

Between 2019 and 2023, there were over 5,000 reported crimes that took place in bookmakers. This included more than 2,000 counts of criminal damage and over 1,000 cases of violence against another person.

Betfred on Gillingham high street

Betfred on Gillingham high street

Contacting betting companies

Throughout the writing of this article, I reached out to numerous bookmakers asking them for a comment.

But it all came to a head when I reached out to Sky Bet earlier this year.

After joining an online chat with a man named Sachin, he provided me with an email address that I could use to contact a representative of Sky Bet.

Part of my conversation with Sachin

Part of my conversation with Sachin

That email proved to be 'invalid.'

I then went on to another online chat where I was matched with a man named Christopher.

He again, gave me an email I could use.

Once again, it proved to be 'invalid.'

Rinse and repeat this process a few more times until I finally got an email address that I was able to send emails to.

I was promised that I would have a response within 24 hours.

It has now been over 45 days without a response, despite me following up.

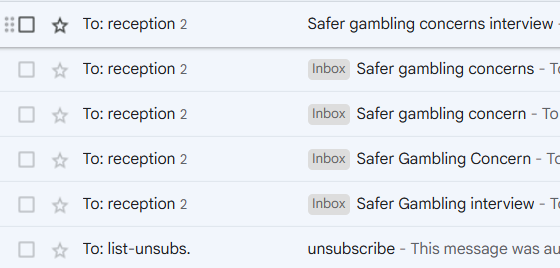

Emails I sent to Sky Bet

Emails I sent to Sky Bet

Whilst I was originally dismayed by this, I think it shows more about certain companies than meets the eye.

Bookmakers do not love to talk to journalists about their dealings. It is their weak spot, and a good businessman knows not to show their Achilles heel.

But throughout this article, it has also been shown that they are not doing enough to help support their customers.

The £5 spin rule that came into effect in late 2024 is a step in the right direction, but as Paddy Power co-founder Stewert Kenny said, "the speed of the games is what makes them addictive."

Simon, Neil and David had to endure years of pain and suffering. But they are just three of thousands of people who struggle with gambling addictions.

"If we remove a lot of the accessibility, then people won't associate gambling with watching sport live or having a bet. We have millions of people in the UK betting, and they need that awareness and accountability of what that looks like. I think we have buried our heads in the sand with it."

If you or anyone you know needs help with a gambling problem, contact these groups below.

- SupportLine - 0121 622 8181