ON THE BORDER OF WAR AND PEACE

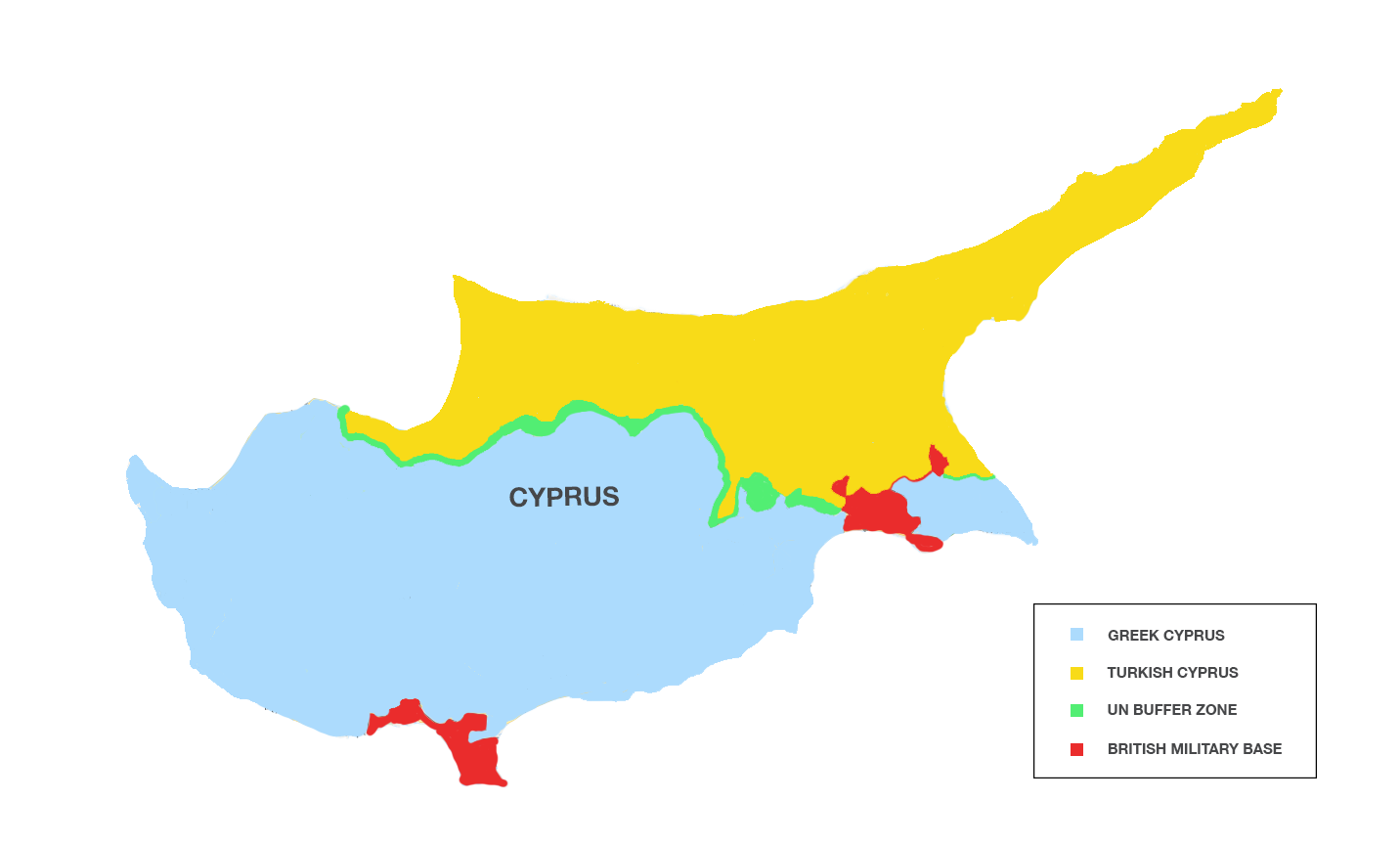

In the Mediterranean sea lies an island that was ripped apart by a conflict that, after 55 years, has yet to be resolved. But with peace negotiations at a halt, will Cypriots finally be able to find peace?

By Isabel Müller Eidhamar

The UN in Cyprus is the longest peacekeeping mission in the world, having served on the island for more than 55 years, in which thousands of people have lost their lives and even more have been displaced from their homes.

Nicosia remains the only divided capital in the world. Attempt after attempt to find peace has failed, with the best diplomats in the world unable to hack the crisis. Today Northern Cyprus remains unrecognised by the international community.

The people who lived through the war are dying out, with the new generation of Cypriots deprived from learning about the conflict in school and peace activists at the forefront of a solution are losing hope.

Today more than 2000 Cypriots are still listed as missing persons; lost in a war that has never been resolved.

But with the healing of time, can Cypriots overcome the things that divide them and be united once more?

AN ISLAND DIVIDED

ANDONIS AND OZEL PART I

"Mr Ozel what in the world are you doing here?"

The man looks up at the young Greek Cypriot soldier that has just spoken to him.

It is the summer of 1974 and his peaceful life in Limassol has been brutally awoken by the cruel hand of war. Together with his wife and 9-year-old son, he and the rest of the Turkish Cypriots in his village have been forcefully gathered by Greek Cypriot military.

"We are just being kept here without knowing what will happen to us," Ozel replies, squeezing the hand of his wife Yuzel, who tightly hugs their son to her chest.

"I know you, you used to help me," the young soldier, Andonis says, smiling. He looks around to see if any of the other soldiers have heard their conversation.

It is a dangerous time for the two men to be friends. People who used to be close neighbours have turned into enemies. The war between the armed military forces has forced many to part ways, and the pain and loss of loved ones stuck in the middle of the bullet storms has crucified all hope that they can live together in peace.

Andonis looks around again nervously, before signalling to Ozel and his family to follow him.

"I want to help you. You are my friend," he says without looking back.

He takes them in his car and drives them back to their home. When they are inside he looks Ozel seriously in the eyes:

"Whatever you do, don't leave. I will be back at nightfall."

Ozel doesn't have time to say thank you, because with that Andonis is gone.

He arranges for them to leave for the North the following morning, and as they hug goodbye, Ozel's eyes fill with tears. The young soldier has risked his life trying to save theirs.

They leave the next morning.

Ozel's wife Yuzel dresses up as Greek Cypriot woman, hiding her nose in a huge Greek newspaper as a car drives her across the border.

Ozel's son is sent with a a British couple pretending to be their little boy, and Ozel is left with no other option than to curl up in the trunk of a car, as a Greek Cypriot man drives him towards the Paphos Gates in Nicosia.

Eventually the driver stops and opens the trunk where Ozel is hiding.

"This is all I can do for you," he says. "You will have to run from here."

Ozel runs. He runs as fast as he can towards the North, only a few hundred metres separating him from safety.

Then a Greek Cypriot guard sees him and starts yelling: "STOP! Stop or I will shoot you!"

Ozel doesn't stop, he just keeps running. His little family is on the other side, and he doesn't want his son growing up without a father.

Tired and breathless he makes his way to safety. The Greek Cypriot guard fires no shots. He is one of the lucky ones.

Nearly 200,000 Greek Cypriots and 40,000 Turkish Cypriots are forced to flee in the months that follow.

In the next ensuing decades Ozel will often wonder about the man that saved his life.

It will be 30 years until the two friends meet again.

NO MAN'S LAND

The war that ripped Cyprus apart in 1974 left the country's fate undecided. Thousands of people lost their homes, their lives and their loved ones. Dimitris Nickolas and Orhan Atasoy are two of the young boys whose life was forever changed by those warm summer days in July and August.

The boys grew up on opposite sides of Cyprus, unaware of how the events that unfolded between 1960 and 1974 would spin their seemingly different lives onto the same path. Orhan was a 6-year-old Turkish Cypriot from the capital Nicosia, spending the summer with his grandparents in the mountain village of Günendere on the south-eastern slopes of the Kyrenia range. Dimitris was a 16-year-old from the rural fishing village of Ayia Napa, spending his summer hunting for calamari with his three brothers and helping out in the potato fields.

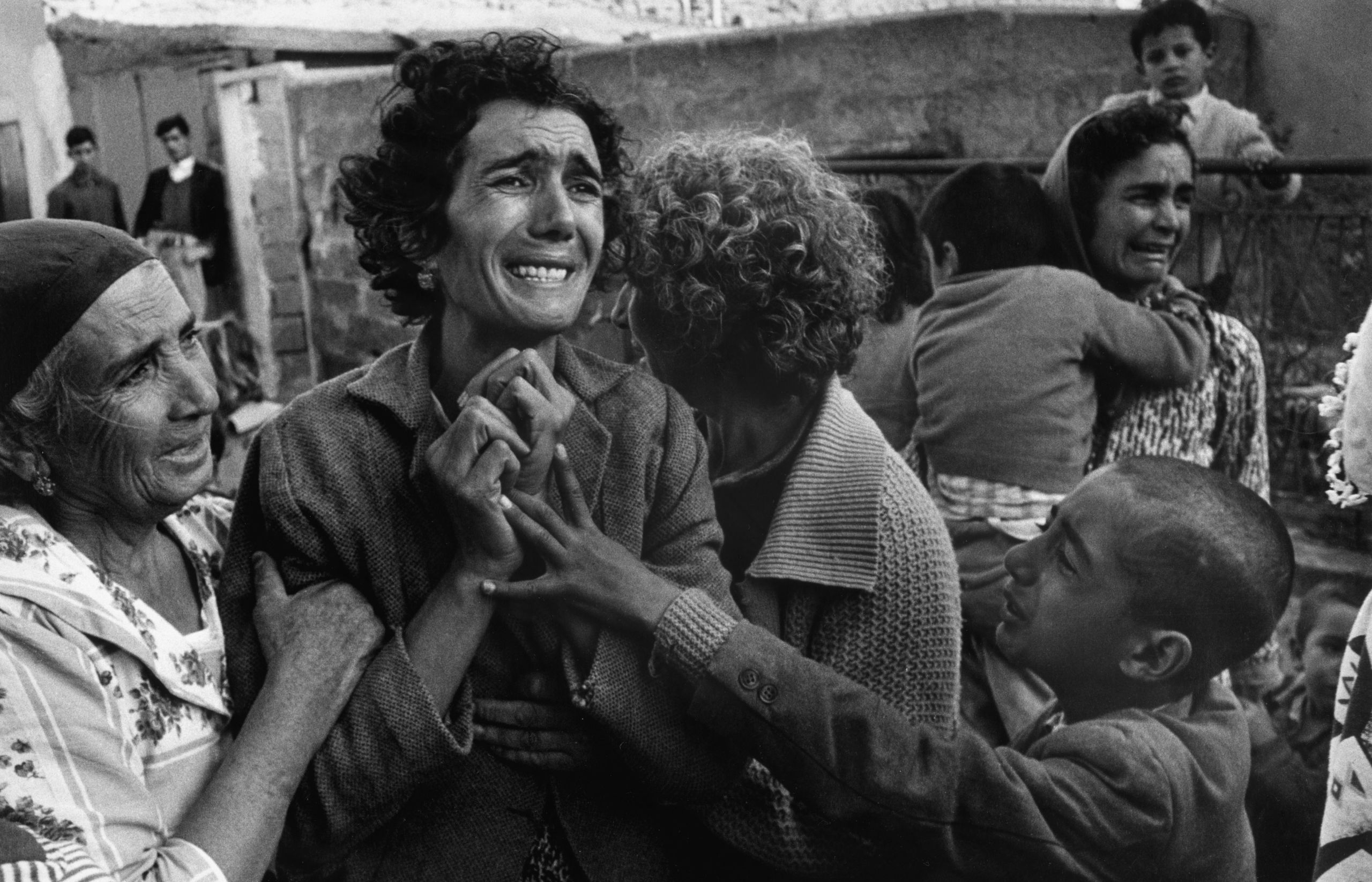

On the left: Dimitris working in his family's potato field. On the right: six-year-old Orhan.

On the left: Dimitris working in his family's potato field. On the right: six-year-old Orhan.

It had been a turbulent year in Cyprus with multiple clashes between EOAKA-B members and the Turkish Cypriot guerrilla group TMT. The leader of EOAKA-B, Georgios Grivas, died of a heart attack in January 1974, causing the group to fall more directly under the control of the military junta in Greece. On July 15th EOAKA-B launched a military coup against President Makarios aimed at enosis, a union with Greece. The President escaped to London unhurt, and on July 20th Turkey evoked the Treaty of Guarantee and mobilised into the North.

Thousands of people had to flee their homes, leaving everything dear behind. Tourists were evacuated from the island. Cyprus had become a warzone, and a no man's land swallowed 180km of the Mediterranean pearl. This is today the UN bufferzone. The former celebrity summer paradise, Varosha, in Famagusta, was turned into a ghost town. Shoes still lay by the hotel entrances, and forgotten passports remain somewhere inside the harrowing hotel rooms, now only visited by curious birds peeking through bombed windows.

Varosha has remained under Turkish control since 1974 when its 39,000 residents were forced to flee. The bombed hotels still stand today as a painful reminder of the past.

Varosha has remained under Turkish control since 1974 when its 39,000 residents were forced to flee. The bombed hotels still stand today as a painful reminder of the past.

DIMITRIS AND ORHAN

The boys found themselves abruptly thrown into the world of grown-ups. What they experienced during the war shaped them forever.

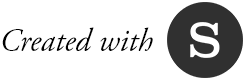

Cypriot children, photographed by Richard Chamberlain in 1954.

Cypriot children, photographed by Richard Chamberlain in 1954.

Orhan´s story

Orhan Atasoy was only 6-years-old when the war broke out, blissfully unaware of the turmoil ravaging his beloved country. But the human horror he experienced would be burned into his mind forever.

Orhan and his sister Fatma playing in the Troodos Mountains (1973).

Orhan and his sister Fatma playing in the Troodos Mountains (1973).

Summers in Nicosia were humid and hot, with temperatures reaching up to 50 degrees. The summer of 1974 was no different. Every summer Orhan's parents would send him away to his grandparents in Günendere, a small Ottoman mountain village. The heat in Nicosia was not a good place for the adventurous little boy, who most of all wanted to play with his cousins and climb in trees.

"It was like heaven. In the city there were limited places to play around, but when I went to my grandfather's village I could be in nature. I was free there."

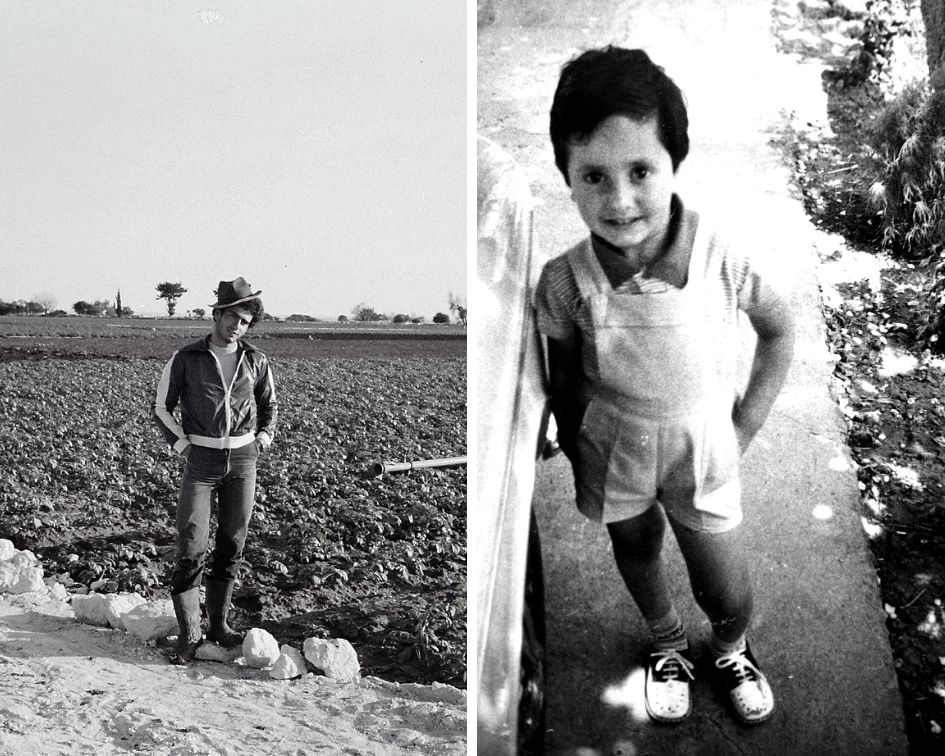

A picture of Orhan in the Trodoos Mountains in 1973, one year before the war.

A picture of Orhan in the Trodoos Mountains in 1973, one year before the war.

The summer had started like any other. Days were filled with childlike imagination and delicious food. The village was tranquil and peaceful, the older men would play backgammon on the cafe terraces, the women would meet to chat and children would play in the streets. It was as if the people were unaware of the war that was about to erupt. In mid-July everything changed.

A old family photograph of baby Orhan and his older sister Fatma from 1968.

A old family photograph of baby Orhan and his older sister Fatma from 1968.

All the men who knew how to use a gun armed themselves and created a defence around their beloved village. The children, women and elderly hid inside their houses. When the night came, the fear grew. Orhan did not understand much, but the sound of bombs and airplanes above his bedroom roof scared him. As the rumour of the Greek troops' advancement spread, Orhan and the other villagers not involved in the defence, went to hide in the village's secondary school.

Orhan reminiscing about the past at the step outside the school where he had been hiding in 1974.

Orhan reminiscing about the past at the step outside the school where he had been hiding in 1974.

It was true what they had heard. When the Turkish troops came to Cyprus on July 20th, EOAKA-B, who held the nearby Greek Cypriot villlage of Peristeronipigi (Alaniçi), captured the three Turkish Cypriot villages of Muratağa (Maratha), Sandallar (Santalaris) and Atlılar Katliamı (Aloda), where they arrested the men and sent them to internment camps in Limassol. In these villages, only 12 to 15 km from where Orhan and his grandparents were hiding, the women, children and elderly left behind were murdered by EOAKA-B men on August 14th when the second Peace Operation from Turkey started, as if verifying a statement made by President Makarios in his dictum written in August 1964:

"If Turkey comes to rescue the Turkish Cypriots, they will not find a Turkish Cypriot to save."

The shock of the Turkish military's advancement caused them to act quickly, and the 126 victims of the mass murders were buried in the mass graves that still remain as an open graveyard today. The youngest victim was a 16-day-old baby, the oldest a 92-year-old man.

That same day, only 12km away, Orhan and the rest had to flee the school where they were hiding as it was no longer considered safe. Orhan was scooped up by one of the adults, who had decided to make a break for the mountains where it would be safer. However, they would not get far.

Orhan outside the school building where he hid in August 1974.

Orhan outside the school building where he hid in August 1974.

"We were running towards the mountains, and then a military car cut the way. We all started to cry."

As they were heading up a mountain path, an armoured car stopped in the middle of the road, cutting them off from safety. Panic struck, and everyone, young and old, began to cry. They believed it would be the last thing they saw.

Little did they know their saviours had come.

A breakdown in communication due to the ongoing war meant that Orhan and the villagers did not know the Turkish forces had come to rescue them.

Orhan had never seen a Turkish soldier before, but as one of them pulled out a Turkish flag and held it aloft to assure them, he and the others were overcome with relief.

"Everyone started crying, and embraced the soldiers. We were so happy we had survived."

While Orhan did not completely understand what was going on at the time, the evident joy on the adults' faces and the tears streaming down their cheeks, reassured him that he would be safe.

The Turkish soldiers brought them back to Günendere, where Orhan soon would be reunited with his father Özkan.

Özkan was a member of TMT, the Turkish Cypriot guerilla force. He was involved in a great deal of questionable actions, which he would later regret on his deathbed and which caused him to have a turbulent relationship with his son.

"It was the only time I saw my father and cried. I hugged him, I was so happy to see him."

By his father's side Orhan drove home to Nicosia flanked by a military escort. On the way home Orhan would come face to face with the horrifying results of the conflict.

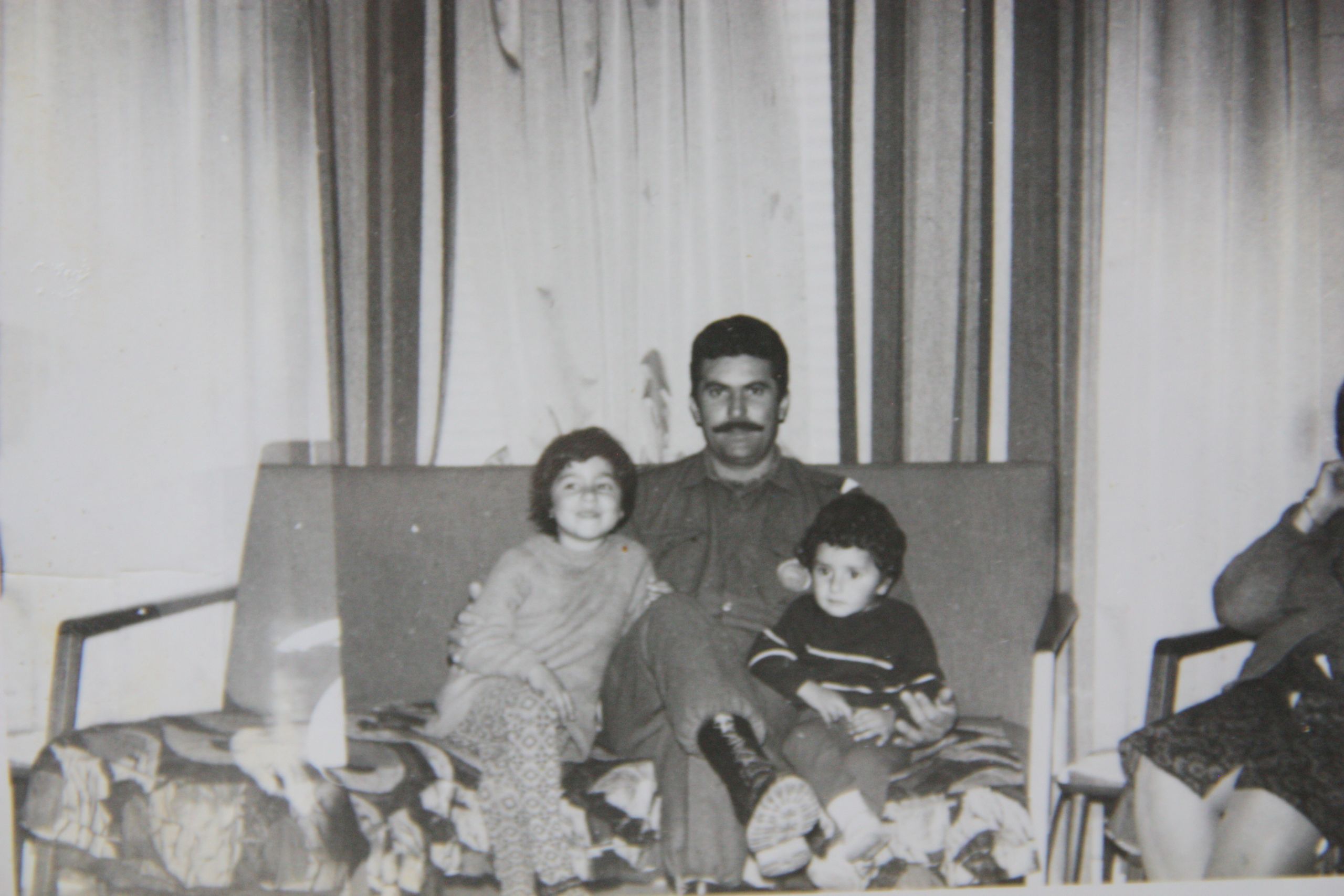

Orhan pictured with his father Özkan and his older sister Fatma, 1971.

Orhan pictured with his father Özkan and his older sister Fatma, 1971.

As they neared the outskirts of Nicosia, all Orhan saw was dead bodies along the road. They were almost unrecognisable: bloated and disfigured by the heat.

Somewhere along the road the cars stopped, and the soldiers got out. They hurriedly tried to move the bodies into large pits dug at the site. It was impossible to say whether these bodies were Greek or Turkish Cypriot, so they were laid to rest together. Orhan's eyes were quickly covered by his father's hand. This was not something any child should see, but the memory would be burned into Orhan's mind forever.

Orhan Atasoy says people only kill for their egos, and doesn't think that it will ever change.

Orhan Atasoy says people only kill for their egos, and doesn't think that it will ever change.

45 YEARS LATER

Today Orhan lives in a rented house with his wife and their adopted stray cats and dogs. His experiences from the war shaped the rest of his life.

What he saw on his way home to Nicosia and his early memories of his father's involvement in the TMT had caused him to despise weapons, and during his mandatory military service at eighteen Orhan had to be forced to carry a gun.

"I always hated it because it feels cold. It is killing your feelings. When you are holding it you think that you have the power to kill."

After the war people began asking what secret groups, such as EOAKA-B and TMT had done, and Orhan began to question his father.

It was not until his deathbed that Özkan would confess his crimes.

"He was so sorry when he was dying. He said he wished he had not done so many things."

A photograph of Orhan's father Özkan during his time with TMT.

A photograph of Orhan's father Özkan during his time with TMT.

Even 45 years on Orhan still holds the hope that Cyprus will be united once again.

"Cyprus belongs to Cypriots. Just leave this island alone to the people who love it. Let them decide what to do."

"Cyprus belongs

to Cypriots"

Orhan Atasoy

DIMITRIS' STORY

On the south-east coast of the island another Cypriot boy was about to see his whole village change in front of his eyes. Dimitris Nickolas, an adventurous and philosophical 16-year-old from countryside Ayia Napa, was about to witness the birth of one of the hottest European party destinations, and perhaps, the death of his beloved fishing community.

"As a teenager living in a small fishing village we were happy and careless."

Prior to 1974 Ayia Napa was a tranquil and charming little fishing village whose population made a living of fishing and farming. It was a place far removed from the jet-setting tourist crowds that each year flocked to Famagusta, only a short forty-minute drive away. It was here that Dimitris grew up together with his three brothers Yiannakis, Emilios and Andreas.

At that time there was close to no tourism in their village, and the only TV available was found in the village Kafenion, a gathering place where the men of Ayia Napa would play backgammon, cards and gossip.

An old photograph from a kafenion in Ayia Napa.

An old photograph from a kafenion in Ayia Napa.

The summer of 1974 changed everything. Though the villagers knew something was brewing following the military coup on July 15th, the Turkish invasion still came as a shock. Just like with Orhan, Dimitris' beloved village would soon change: not by violence and mass graves, but by the invasion of mass tourism.

The message that the north had been seized came over the radio on the morning of July 20th, and it has since remained a painful memory for most.

Inside their bedrooms the boys could hear the desperate cries outside and the deep sorrow many Greek Cypriots felt in losing what had been their home for so long. When Dimitris and his brothers went to the window they could see all the people gathering in the neighbourhood, and the heartbroken mothers waving goodbye to their seventeen- and eighteen-year-old sons being loaded on to trucks and sent into the war. Had Dimitris been only one year older, he would have had to go and fight with the rest of the men. Many of them never returned.

"Being a kid you still realise that something bad is happening."

As the Turkish troops advanced, fears grew that they would reach Ayia Napa, and Dimitris' father Nickolas decided the family were no longer safe, and that they too had to leave. A family friend let them stay in his house in Limassol until it was safe to return.

An old photograph of one of Ayia Napa's main street, taken before the devlopment that followed post 1974.

An old photograph of one of Ayia Napa's main street, taken before the devlopment that followed post 1974.

A few days later when the Turkish soldiers stopped marching forward, the family went home to Ayia Napa, where thousands of Greek Cypriot refugees who had fled the north had come begging for help.

One of the refugees from Varosha wrote in a blog how he had to flee on the back of a truck with his family, leaving behind his aunt who refused to leave her home despite her husband being killed by TMT. They, as many others, were taken to Ayia Napa, where the police were trying to restore order amid the chaos of the hundreds of refugees waiting for help. Eventually his family was offered to take over a supermarket and apartment formerly owned by a Turkish Cypriot family, who like them, had to flee the war.

"We had little cash or any items of value and it was impossible to take everything we owned with us. We would have to go leaving everything we had worked for behind in the hope that the situation would improve and that we'd be able to return home."

For Dimitris and the rest of the villagers in Ayia Napa, the masses of refugees changed the face of their village, and in the space of only a few days, it's population, which in 1972 counted to about 200 people, more than tripled. Soon the holiday-makers that had been thriving across the bay in Famagusta, would invade the small fishing village.

Dimitris (far right) dancing a traditional Greek Cypriot dance for tourists at a taverna.

Dimitris (far right) dancing a traditional Greek Cypriot dance for tourists at a taverna.

Dimitris' father had until then made a living as a fisherman, and his small light-blue fishing boat was his greatest pride.

Tourism started to boom in Ayia Napa following the war, as a result of an embargo placed on North Cyprus, which shut the borders to former holiday paradise Famagusta until the borders were opened again in 2003. Dimitris' family also started to earn good money of their humble farming land. But the people of Ayia Napa quickly learned that tourism comes with a price...

45 YEARS LATER

Much has changed in Ayia Napa since 1974. Today the former village has become a town, and many of the local residents have sold their properties to developers and moved into the hills. The village that for centuries had made its income off farming and fishing saw tourism take over as the principal industry.

Scenes from Ayia Napa, 2018.

Scenes from Ayia Napa, 2018.

As it sprung from a rural farming village to the new Ibiza, the local people that were born-and-raised would soon be outnumbered by tourists, EU workers and Russian migrants. Dimitris misses the early days of tourism in Ayia Napa, and is worried about Cypriots becoming a minority in their own country.

Dimitris misses the old days in Ayia Napa and close ties he used to share with the other villagers.

Dimitris misses the old days in Ayia Napa and close ties he used to share with the other villagers.

Dimitris is critical to a solution being found, and is disappointed that the EU have not done more to assist their member state, the Republic of Cyprus, in solving the problem. He hopes negotiations soon will be brought back to the communal talks table.

Even after all these years, he insists he still views Cyprus as one island, despite the fact that it has been separated since 1974. He believes that the reason why Turkey, after numerous attempts, remain outside the European Union, is due to their unwillingness to solve the problem.

"I think it's a disgrace that Cyprus still today remains an island under military occupation. Europe should do more to assist us in solving this problem."

"The key to the

Cyprus problem

I believe lies in the

Turkish' hands."

Dimitris Nickolas

THE CRISIS OF PEACEKEEPING

The UN has played an active role in the Cyprus Crisis ever since the conflict began, wearing out generations of blue berets. What started as a 'temporary' mission of three months has turned into a permanent part of the island's identity. But after 55 years, is it time to leave?

UN troops in Cyprus in 1964, photographed by former UN soldier Willy Lindh.

UN troops in Cyprus in 1964, photographed by former UN soldier Willy Lindh.

The UN came to Cyprus in 1964 to prevent further fighting following intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots and to restore normality.

In 1974 the mission was expanded following the military coup in Cyprus and the subsequent military intervention by Turkey.

Since then 21 nations have served on the island, and more than 150,000 soldiers have assisted in supervising the ceasefire lines and providing humanitarian assistance. The UN continues to maintain the 180km buffer zone that runs through the entire island from east to west, separating the Greek Cypriot forces in the south from the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot forces in the north.

The mandate to keep the UN forces on the island has been extended seventeen times between 1964 and 2018, and in January 2019 the decision to extend the mission another 6 months was made.

But with peace negotiations at a standstill, is the UN still serving their purpose?

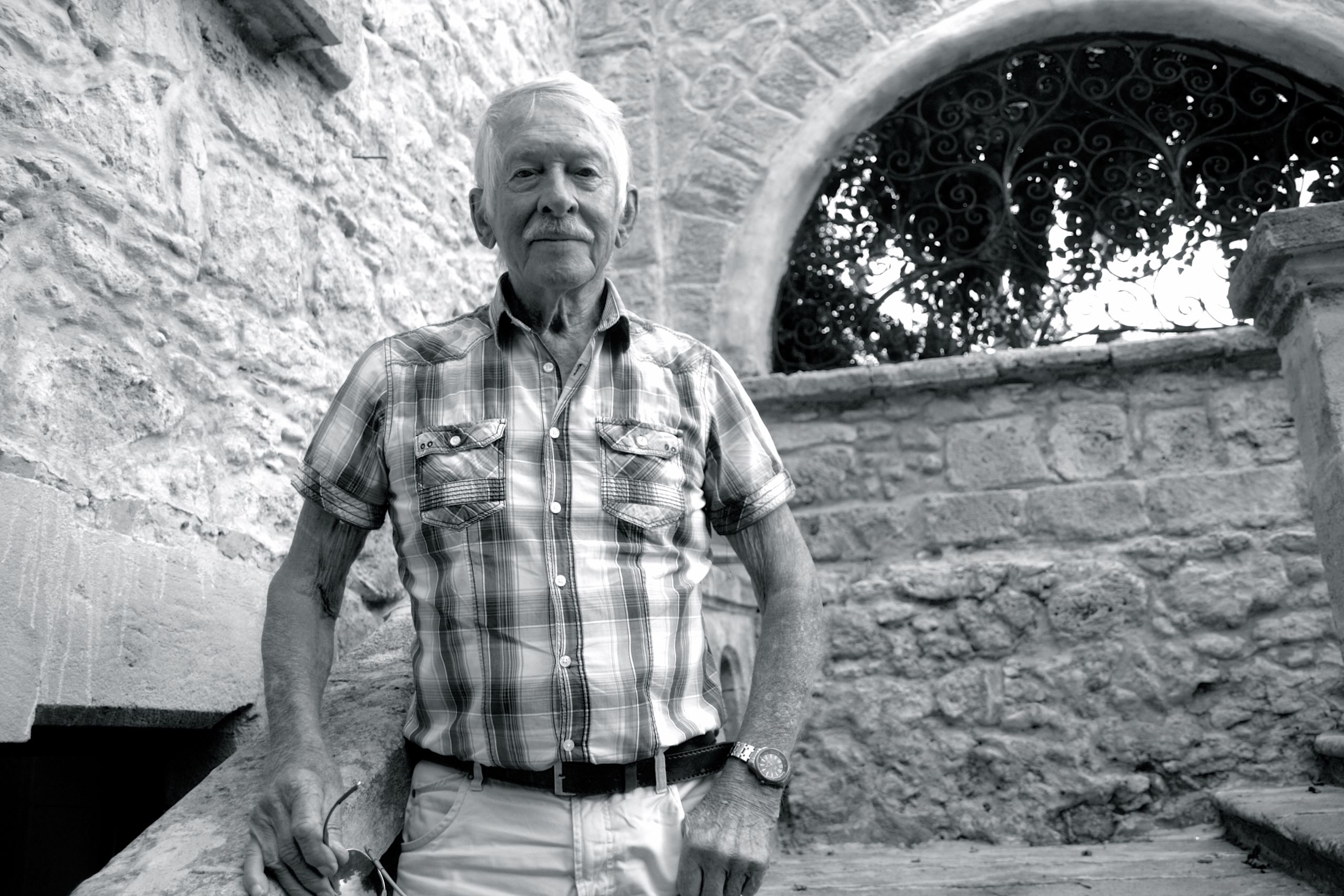

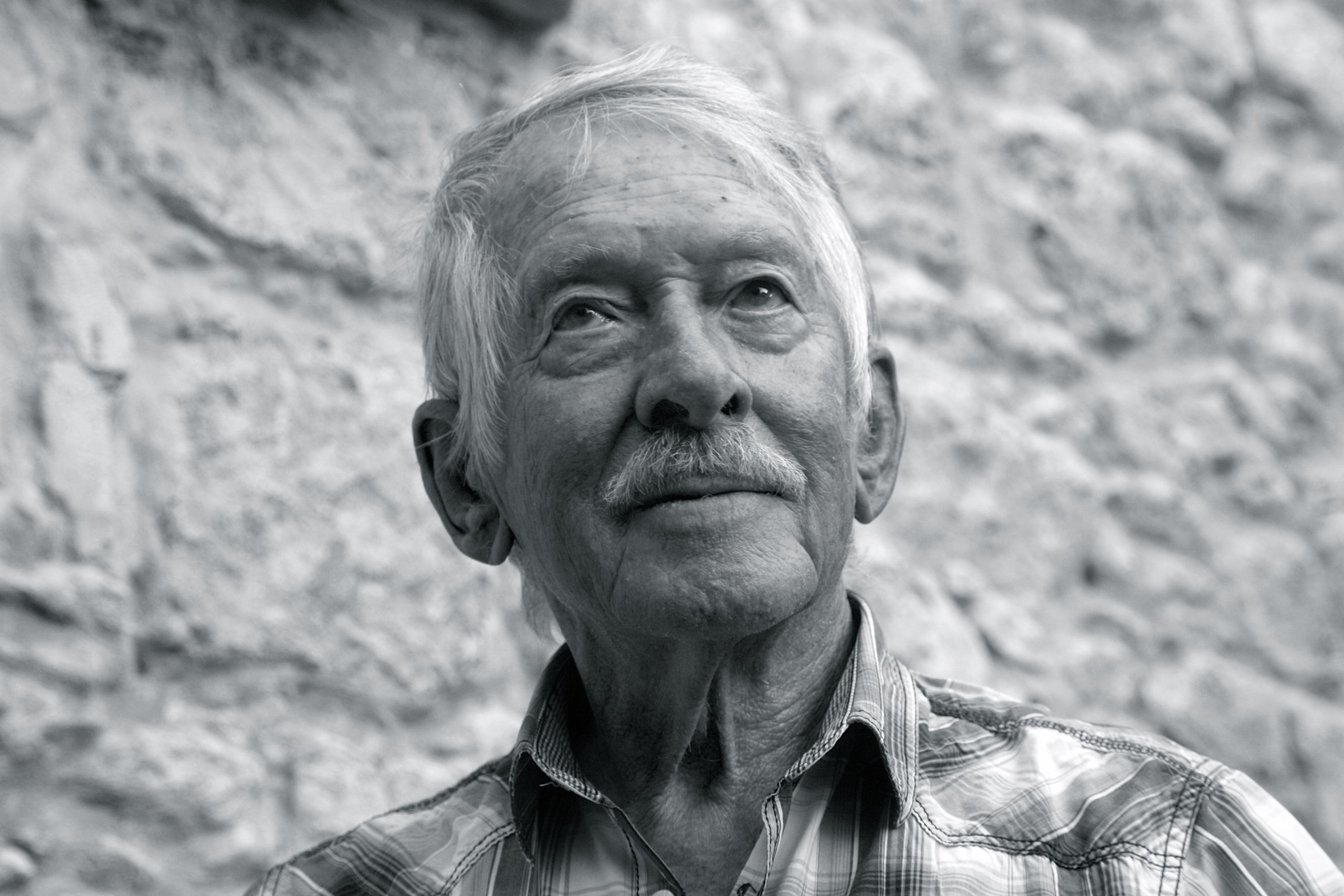

Willy Lindh has been called everything from a traitor to a saviour. As one of the first UN soldiers to arrive in Cyprus in 1964 he would witness the beginning of the war, that ten years later, would split the island apart.

Ever since Cyprus gained independence from Britain in 1960 the island has been tormented by constitutional wrangling, intercommunal violence and hate crime. The constitution, which was created to ensure power-sharing between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority, was suddenly questioned by President Makarios, causing tensions to rise. The violence, murders and feuds would escalate, forcing the United Nations to step in to protect the civilians.

"We arrived at 11 at night with a United States Hercules plane, and even in our first hours [in Cyprus] we felt a very big difference from calm Sweden."

Willy Lindh in Kyrenia, 2018

Willy Lindh in Kyrenia, 2018

Willy Lindh grew up in Stockholm, Sweden, and until 1964 he had never experienced war. He was 27 at the time of his first (and last) mission. Cyprus.

Willy and the rest of the soldiers arrived in Cyprus during the scorching July heat. As a Lieutenant he was put in charge of five Turkish Cypriot villages in Erenköy in the western part of the island. It was the only coastal strip still accessible to the Turkish Cypriots, whose communities had been surrounded by the Greek Cypriot military.

"According to my company commander this [Erenköy] was the worst place on the island."

The year before, President Makarios had proposed a controversial amendment to the constitution that would repeal the power-sharing arrangements between the two communities. A liquidation plan which was later known as the Akritas Plan.

Suddenly Turkish Cypriots found themselves unarmed and defenceless against the Greek Cypriot militia that dreamed of enosis, a union with the 'motherland' Greece. Turkish Cypriot police were disarmed, their communities encircled, and even their politicians were forced out of office. All power over airports, power plants and water supply was given to the Greek Cypriot government, who through the amendment hoped to extradite the Turkish Cypriot minority.

This is when the UN chose to intervene. Willy and the others were tasked with setting up outposts and preventing an escalation of the conflict. They were not allowed to interfere, but were required to report any military action from either side.

"Most of the villagers were untrained farmers and had only light weapons to defend themselves."

Fightings in Erenköy area in the summer of 1964.

Fightings in Erenköy area in the summer of 1964.

700 people lived in the five villages Willy patrolled, many of them women and children. The men in the village were mostly farmers and had no military training, with only shotguns to defend their families from Greek machine guns. Their war had already been lost.

On August 6th 1964, the Greek Cypriot National Guard of 25,000 soldiers, supported by 10,000 soldiers from mainland Greece, bombarded Erenköy with heavy artillery, mortars and cannons. Many of the Turkish Cypriot villagers were killed or wounded.

"I remember that I thought that the Greeks weapons rearmament was excessive and unreasonable given that they met such a weak and poorly equipped enemy."

The UN had withdrawn their forces to the mountains before the attack took place, leaving behind the villages they had vowed to protect. Only Willy and a dozen of his soldiers had chosen to stay.

From the UN headquarters the message was clear: Stay out of the fighting, and do not under any circumstances, interfere.

In a few days, four out of the five villages had been conquered by the Greek Cypriots. But during the villagers darkest hour, an unexpected protector would come to their rescue.

"We really tried to stop them, but we did not have the authority. They [the Greek Cypriots] were definitely favoured by the United Nations."

Willy Lindh says the Greek Cypriots were favoured by the UN and the international community.

Willy Lindh says the Greek Cypriots were favoured by the UN and the international community.

AT WAR WITH NEUTRALITY

Late in the afternoon on August 8th multiple Turkish fighter jets attacked the Greek forces that had encircled Erenköy. The aerial assault lasted several hours, and by the end, defeated Greek troops were forced to retreat from the village.

Only with Greek troops out of the village, the UN returned to the duties they had left behind.

Following the surprise turn of events, the civilians were evacuated from the village. However, many of the Turkish Cypriot women refused to leave their beloved Erenköy. Instead they hid in nearby caves to protect themselves from the gunfire.

A UN soldier repelling from a helicopter, Erenköy, 1964.

A UN soldier repelling from a helicopter, Erenköy, 1964.

The village was still isolated from the rest of the island. Their only connection to the outside world was the open ocean in front of them, where Turkey offloaded boatloads of guns that the villagers could use to protect themselves.

"We knew of course that transporting weapons was the worst thing you could do."

The UN supplied the villagers with food supplies, but emergency healthcare was cut off from them by Greek Cypriot roadblocks. Though the UN helped as best they could with providing medical care and escorting out the dead and wounded, their efforts were not enough.

Then came the word that the nearby village of Lefke was to be attacked by Greek Cypriot troops. That is when some of the villagers approached Willy, asking him to help them smuggle weapons to their friends so they could protect themselves from the inevitable attack.

Together with his colleague Helge Hjalmarson and five other soldiers, Willy agreed to help secretly transport weapons to Turkish Cypriots in Lefke.

In the beginning it went smoothly, and the men faced no issues crossing the roadblocks. But the word spread. Eventually someone decided to snitch on them to the Greek military.

A picture of Willy in his jeep when he first arrived in Cyprus in July 1964.

A picture of Willy in his jeep when he first arrived in Cyprus in July 1964.

They were stopped at a roadblock in their armoured car, and with a truck full of weapons, the crime was hard to deny. The UN were contacted, the weapons handed over to the Greeks and the men were taken prisoner. Willy had no idea how big of a deal it would become.

The UN Secretary General at the time, Kurt Waldheim, was called and woken up in the middle of the night. The UN chief, their battalion chief, the police and the press were all informed, and the men were transported to the British military camp in Nicosia for interrogation.

Within days they were sent back to Sweden, stripped of their honorary UN badges, and thrown into what would become a high-profile trial, which eventually would end their UN careers and send them to prison.

"Our view was that the UN had betrayed the Turkish Cypriots."

PRISON, TRAITORS AND BIAS

Willy speaks about why he believes the UN were biased during the Cyprus civil war in 1964.

Willy speaks about why he believes the UN were biased during the Cyprus civil war in 1964.

Willy had never expected the media circus that would greet him at the arrivals gate at Stockholm Skavsta Airport in the autumn of 1964.

"Traitor!", "weapon smuggler!" and "you are horrible people!", were only some of the abuse the men had to cope with.

Eventually they ended up in trial accused of crime of majesty, an accusation as serious as treason. Willy was facing a potential life sentence of prison labour.

However, their criminal defence lawyer, Ragnar Gottfarb, calmed the court, and the men were sentenced to two years of penalty labour. This was later shortened to eight months.

Willy Lindh photographed in Kyrenia in 2018.

Willy Lindh photographed in Kyrenia in 2018.

Despite losing his military rank that he had invested more than eight years of his life to obtain, his career ending in shambles and being branded as a traitor by millions of people, Willy says he would do it all over again.

"We had seen how those people had been treated. We felt that the United Nations had not acted as they should...I never regretted it and I would do it again."

He often ponders whether the situation in Cyprus could have been different if the UN had acted back in 1964...because is it truly possible to be neutral in war?

The forgotten army

The UN forces in Cyprus (UNFICYP) is the longest peacekeeping mission in the world. Their mandate has been extended 18 times since their arrival in 1964, and in July the question is up for debate in the Security Council yet again. With peace negotiations at a standstill, it raises the question: is the UN still needed in Cyprus?

UN soldier in Cyprus inside an abandoned home in the bufferzone. Photo: Katarina Záhorská.

UN soldier in Cyprus inside an abandoned home in the bufferzone. Photo: Katarina Záhorská.

"No peacekeeping mission should last forever."

When the UN first arrived in Cyprus its mission was to prevent the escalation of violent fighting between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. Today no deadly shots have been fired for decades, and to a stranger's eye the Mediterranean island appears peaceful and serene. The only visible signs are the many border crossings, the ghosted hotels in Varosha and the many military camps spread across the island.

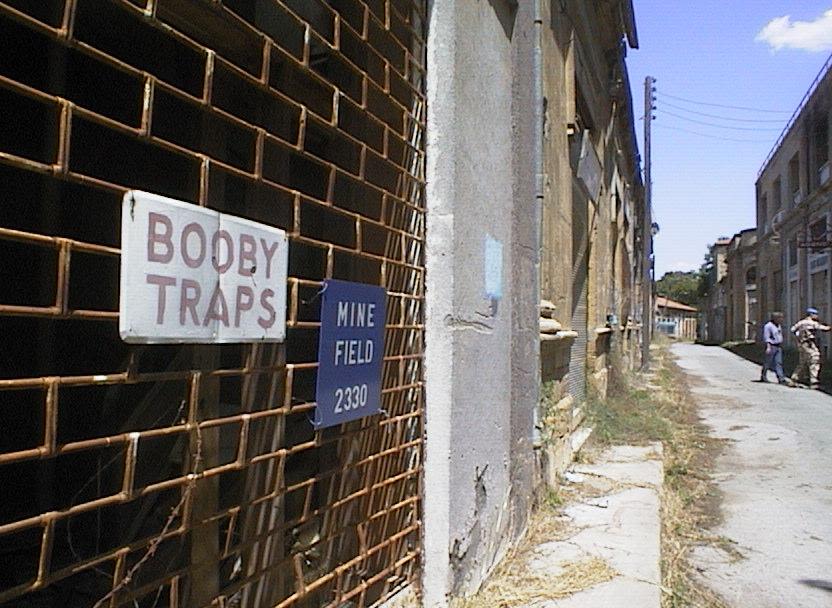

The buffer zone, or so-called green line, that was established 55 years ago has become a prominent part of the Cypriot identity. Today it accounts for more than 3% of the island, spanning more than 180km in length. What remains inside the buffer zone seems frozen in the past, ghosted, abandoned and isolated for the developed world outside its gates.

The only inhabited buildings past the green line are the UNFICYP headquarter, a couple of offices, negotiation rooms and sleeping bunkers for the soldiers who train there every day. Armed UN soldiers check the registration number of all cars entering the seemingly frozen world.

The first sight that greets visitors is the decrepit petrol station a short drive from the main gates. The sign outside the building still showcase the price of petrol the day it was abruptly left behind in 1974. Today nature has taken a hold of its walls, engulfing the pillars and petrol pumps with branches and weeds.

An abandoned carpark in the bufferzone in central Nicosia. Photo: Roman Robroek.

An abandoned carpark in the bufferzone in central Nicosia. Photo: Roman Robroek.

Over the past 3 years, Aleem Siddique has spent his days here working as the official spokesperson for UNFICYP. In that time he has witnessed the peace-talk progress that in 2017 would bring Cyprus within touching distance of the solution, that for more than forty years had remained a distant dream.

Aleem Siddique outside the UNFICYP headquarters in the Nicosia buffer zone, 2019.

Aleem Siddique outside the UNFICYP headquarters in the Nicosia buffer zone, 2019.

"The most important change I have seen since I came to Cyprus is the recognition that the current status quo cannot continue," Aleem says.

Today one of UNFICYP's key roles is to facilitate and lead efforts to assist the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot government in reaching a comprehensive agreement.

"Making peace is never easy business," Aleem says, "if it was we would have solved the Cyprus problem 55 years ago."

"You are dealing with some of the most difficult issues. Issues that go to the heart of each community."

During the Crans Montana negotiations in 2017, the closest Cyprus has ever come a settlement, UNFICYP played a central role, working closely with the UN Special Advisor on Cyprus and main diplomat, Espen Barth Eide.

In the lead-up to the talks UNFICYP's mandate was extended multiple times, because it was argued they were a crucial part of the negotiations. However, when the talks broke down, the question on whether the UN still served a purpose arose yet again.

Despite the criticism Aleem believes the Cypriot people think they are needed on the island.

"We are very grateful for the support we receive from both communities. There is a strong understanding of why the presence of the UN is required, and I think there is an appreciation for the role the UN can play."

More than 7,000 mines still remain in the ground in Cyprus despite years of calm conditions. Photo: Katarina Záhorskà

More than 7,000 mines still remain in the ground in Cyprus despite years of calm conditions. Photo: Katarina Záhorskà

It costs £42m a year to keep the UN forces in Cyprus. Almost half of which is funded by the Republic of Cyprus (£13.8m) and Greece (£5m).

Aside from facilitating talks, where UNFICYP has a permanent negotiating team constantly working on what a possible deal would look like, its troops also serve an important role.

On a daily basis the troops supervise the cease fire lines established in 1974 and maintain control over the buffer zone. Despite nearly no violations of the ceasefire since then, UNFICYP records an average of 1,000 incidents in the buffer zone each year.

"We have challenges on a daily basis in patrolling the buffer zone," Aleem explains.

"We rely on good and effective relationships with the opposing military forces to address any of the challenges that arise during the course of our work with them."

UN car patrolling the buffer zone in Nicosia. Photo: Katarina Záhorská

UN car patrolling the buffer zone in Nicosia. Photo: Katarina Záhorská

Over the past 55 years more than 150,000 troops have served in UNFICYP, with 888 currently serving on the island. The United Kingdom and Argentina have been the largest troop contributors, and on average UNFICYP's military and police forces rotate every six months, year or every two years depending.

Today over a thousand people, both Greek and Turkish Cypriot, still live inside the buffer zone.

"Most people think of a buffer zone as a dead zone, but the reality is that a buffer zone is a living, breathing thing," Aleem says.

There are schools, villages and factories all within the buffer zone. In these areas the UN peacekeepers work around the clock to give its inhabitants access to move, in liaising between the opposing forces and by maintaining law and order. They even help facilitate religious services in mosques and churches for those who chose to stay in their homes when the war broke out.

However, most of the buffer zone still remains dead and abandoned.

Only a short drive from Aleem's office is the old Nicosia International Airport, left desolated since 1974.

On its deserted runway an old Cyprus Airlines passenger jet still stand covered in dust, its old logo deteriorated by years of blasting sun and bullet holes in its window as if taken out of a horror film. The scene is eerie. Broken glass, heaps of barbed wire. Sprouting weeds is the only sign of life in the airport that back in its glory days hosted stars such as Grace Kelly and President John F.Kennedy. Many of the huge led-light letters that used to spell out the name on top of the building have disappeared just as the many tourists that used to roam its now deserted arrival halls.

A back-street inside the UN buffer zone. Photo: Katarina Záhorská.

A back-street inside the UN buffer zone. Photo: Katarina Záhorská.

The UN in Cyprus have entered its 55th year of service to the Cypriot people, having maintained a neutral approach since they first arrived. A time that now, seems a world away.

Despite Willy's criticism of their approach to the crisis in 1964, Aleem withholds that the UN are unbiased when it comes to the Cyprus conflict.

"The unique selling-point of the United Nations is that we remain impartial, and we value our impartiality," Aleem says, "It is the most important feature that we can offer in a divided island such as Cyprus."

However, some critics claim that the money spent on keeping UNFICYP forces in Cyprus could be better spent in war zones where people are still being killed.

"The sad reality is that there is conflict taking place all over the world, and there is a need for peacekeepers. Where those peacekeepers are deployed and how long, is really a matter for the Security Council."

"Any organisation in the world, including the UN, will have a certain tendency to just continue. So it is helpful for someone to say, 'are you doing the right thing? And why are you doing this after (55) years?'"

On July 31st the Security Council will decide whether to extend the UNFICYP mandate yet again. If extended, it will be the nineteenth time the decision on whether or not to withdraw the UN forces in Cyprus has been put to question.

"I hope that Cypriots will realise that they have far more that unites them than divides them," Aleem says.

Until then, the UN buffer zone remains as it was left in 1974: desolated, untouched and abandoned.

THE DIPLOMATIC GRAVEYARD

Cyprus has seen countless attempts at getting a peace agreement signed since the Green Line was established by the UN in 1964. The conflict has frustrated generations of diplomats and negotiators. In duration and complexity, it has been compared to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Is Cyprus a diplomatic graveyard, or could peace be only pen-strokes away?

Espen Barth Eide is the man who has come the closest to breaking the deadlock. After the failure of the Annan Plan in 2004 there was little hope of a unification, but with the joint declaration being signed in 2014 and a change of leadership in the north, it seemed a new opportunity was just on the horizon.

"The current situation is unacceptable and must be overcome...the region needs this and it is so close that to miss this opportunity would be a historic failure."

Espen Barth Eide speaking at a UN conference. Picture: United Nations.

Espen Barth Eide speaking at a UN conference. Picture: United Nations.

THE ROAD TO CRANS MONTANA

Espen Barth Eide was working in the World Economic Forum in Geneva, Switzerland when UN Secretary General at the time, Ban Ki-moon, first approached him about taking on the Cyprus mandate.

"The UN quite smartly said we don't know if there is enough meat here to really have a full-time mediator job, so they came to me and said, listen Espen, we want you to do what you are doing, but can you have a look, and consider this mandate" he explains.

Norway has been involved in many peace processes since the 1990s, from mediation in the Sri Lankan civil war, Sudan and Colombia to being a facilitator in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, peace efforts in Afghanistan and reconciliation efforts in Somalia. Eide already being a seasoned diplomat and former Norwegian Foreign Minister seemed the perfect replacement for Alexander Downer, who stepped down as the UN advisor on Cyprus to take on the role as the Australian ambassador to the UK.

The Cyprus mandate would be a part-time role with a focus on restarting formal negotiations and find a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus problem that would suit both sides. No one could have anticipated just how important this role would become.

"I considered that for a while, and consulted people I knew, and I said, yes, I will give it a try," Eide recalls in his Oslo parliamentary office.

He is back where he started, as a member of Parliament in snowy Oslo, a world away from sunny Cyprus.

"It is extremely important to understand there are more truths than one," he says. "The mature approach would be to say this was tragic, this was a collective tragedy, brought about by several developments, and there were guilty people on both sides."

Espen Barth Eide with UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon

Espen Barth Eide with UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon

It has been five years since August 2014, when Eide first arrived in Cyprus. His first port of call was the hydrocarbon crisis that had blown up the previous winter. Petroleum had been discovered in the ocean around Cyprus, and a feud erupted between the two sides about who had the right to explore the findings. The Greek Cypriot government granted licenses for exploration to international companies, prompting North Cyprus, supported by Turkey, to start exploring the seabeds with seismic vessels. This was met with uproar in the south, who argued they were the ones who legally owned the petroleum, as they are a recognised state. On the other hand, Turkey demanded the Greek Cypriots postponed drilling until the Cyprus problem had been solved.

However, in 2014 the oil prices fell radically, and exploration was no longer an attractive proposition. Eide's experience at the World Economic Forum would come in handy, and allowed an understanding to be reached quickly.

"It was quite helpful, because it gave a lot of access to the big energy leaders," he explains.

It would be his first success in mediating between the two, and in the spring of 2015 it was finally agreed that formal peace talks would resume with Greek Cypriot conservative leader Nikos Anastasiades and Turkish leader Derviş Eroğlu, from the hard-line right wing.

However, a surprising power shift during the 2015 general elections in northern Cyprus would prove to have massive impact on the talks.

Grafitti on a sidestreet of the border crossing Ledra Street in Nicosia.

Grafitti on a sidestreet of the border crossing Ledra Street in Nicosia.

On April 26th 2015 the results were clear, independent candidate, Mustafa Akinci, had won the election with a 60% lead, replacing Mr. Eroğlu as president. This was huge news for people supporting a unification, and after Eroğlu had failed to unite right-wing supporters, Akinci was seen as a breath of fresh air. After the victory, Akinci told the joyful crowds at his rally: "We achieved change and my policy will be focused on reaching a peace settlement. This country cannot tolerate any more wasted time."

"This country cannot tolerate any more wasted time."

The power shift would be a breakthrough. Mr Akinci had served as the Mayor of north Nicosia between 1976 and 1990, during the aftermath of the war, and had high approval ratings in the south.

An old abandoned home in old town north Nicosia.

An old abandoned home in old town north Nicosia.

After the division of the city in 1974, Nicosia still remains the only divided capital in the world, which after the war faced similar issues as Berlin did in 1945. The city, which was built as an entity, suddenly found itself struggling with how to handle the division of the transport, sewer and water systems, and electricity. The systems, which were once all connected, were suddenly divided, something that caused huge practical problems. Due to this mayor-level cooperation became crucial, and Akinci was remembered as a good Turkish Cypriot as he had been accommodating and positive to cooperation in those early days.

"There are memories of him [Akinci] as a good Turkish Cypriot, so he had a very high approval rating in the south. And with him and the helm and with the gas crisis behind us, then only started the real series of talks," Eide recalls of the time.

Espen Barth Eide together with President Nikos Anastasiades (left) and President Mustafa Akinci (right).

Espen Barth Eide together with President Nikos Anastasiades (left) and President Mustafa Akinci (right).

What was unique with the new presidents now leading the talks, was that they were old school-friends. Both Anastasiades and Akinci grew up in Limassol, and with only one year separating them in age, they had gone to school together. This connection would prove itself very valuable as tensions began to rise.

"When we were outside of the negotiating framework, they could laugh with each other and about each other," Eide says, "The first months were extremely promising. We got a lot done. But in hindsight, you can say that we got a lot done because we did the easiest part first."

"The media tends to exaggerate, you know, 'they are the guilty ones, and we are the victims, and justice can only be made if what was done to us is undone'....and that makes it very difficult."

In mid-May talks fully began to pick up momentum. The first months were extremely promising, and the mood was good. Not only was Akinci well-liked for his work as Mayor of north Nicosia, but he was applauded by both Cypriot communities for daring to stand up against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whilst also being able to re-establish the relationship in the name of negotiations. Additionally, Anastasiades had gained a lot of public support, being seen as somebody who was in favour of the Annan Plan back in 2004.

"The two leaders, Anastasiades and Akinci, had in my opinion two formidable excellent negotiating teams, some of the best people on the island."

However, the closer they got to a settlement, the mood changed.

"We steadily moved forward ...more settled this week than last week...but at the same time the mood soured," Eide recalls.

"It is the dilemma of the last mile, because you know more or less what you can get."

At the Cyprus Talks, Palais des Nations, Geneva, January 2017, six months before Crans Montana. Photo: United Nations

At the Cyprus Talks, Palais des Nations, Geneva, January 2017, six months before Crans Montana. Photo: United Nations

"If you tried to focus on nitty-gritty details, you would miss the point, because the point is whether you are politically ready to sell the deal."

In November 2016 Espen Barth Eide, Anastasiades, Akinci and their negotiation teams went to Mont Pèlerin in Switzerland for two rounds of talks regarding territory, one of the most complex issues in the crisis.

"It was a constant sense of, well I am the one giving most," Eide recalls.

On November 22nd the talks broke down without an agreement. It was back to the drafting table.

"The real problem is not between one side and the other, it's between those people who want to live together, and those people who don't want to live together."

CRANS MONTANA

Espen Barth Eide with President Mustafa Akinci (left) and President Nikos Anastasiades (right) in Crans Montana. Photo: United Nations

Espen Barth Eide with President Mustafa Akinci (left) and President Nikos Anastasiades (right) in Crans Montana. Photo: United Nations

In July 2017 the teams were ready for the last round of negotiations. Crans Montana, Switzerland, was the place that was chosen. By the time they left Cyprus most of the deal had been written. But some key issues remained. Among them the controversial topic of security.

Throughout the process one thing became clear to Eide, neither side was ready to compromise.

"There is hardly anybody who would say that they are against a solution, it's just that I am in favour of 'my' solution, not 'your solution," Eide explains.

Espen Barth Eide holding a press conference about the progress of negotiations with Anastasiades (left) and Akinci (right). Photo: United Nations

Espen Barth Eide holding a press conference about the progress of negotiations with Anastasiades (left) and Akinci (right). Photo: United Nations

The first days of the ten-day conference seemed optimistic, Eide recalls. Issues were settled and the public seemed positive. However, towards the end one unsolved issue would flush the past three-years of work down the drain: security.

"When we spoke about security they were equally concerned about it, but they had different answers," Eide explains.

The Greek Cypriots mainly focused on the security of a sovereign state, whilst the Turkish Cypriot position was more concerned about the security of individuals and the community.

"For the Greek Cypriots the first thing should be to get rid of the Turkish influence. Saying, we are not worried about the Turkish Cypriots, we only want the Turks out," Eide says, "but for the Turkish Cypriots, the presence of some troops is a good insurance."

More than 30,000 Turkish troops are still stationed in Cyprus. Their presence has been a big discussion point ever since 1974.

The inability to agree on this point is what would make everything else start to crumble.

"The Greek Cypriot position is to defend the security of the state, to put it a bit bluntly, the Greek Cypriots want to avoid a new 74. Whereas the Turkish Cypriots want to avoid a new 63."

Espen Barth Eide making a statement to the press, 2017. Photo: United Nations.

Espen Barth Eide making a statement to the press, 2017. Photo: United Nations.

The media scene would also prove itself a problem, who in majority, as Eide explains, continued to portray the people on their side, as the victims.

"There is a thin layer of people who would say 'I recognise your pain, and your pain is similar to my pain, and hence we should do something to overcome this'," Eide says.

However, by the nationalist media on both sides this was very much downplayed.

"I much empathise with both sides, because I really understand where they come from," Eide says, "but there was not enough will to overcome that hurdle, which is that, I as a leader, any leader, I have to sell this deal as the best I can get."

On July 7th 2017 the talks collapsed amid anger and recriminations, marking the end of a process seen as the most promising in generations to heal the many decades of conflict in Cyprus.

"I am deeply sorry to inform you that, despite the very strong commitment and the engagement of all the delegations and the different parties, the Greek and Turkish Cypriot delegations, Greece, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, as an observer, and, of course, the United Nations team, the Conference on Cyprus was closed without an agreement being reached."

THE FUTURE OF CYPRUS PEACE TALKS

"Now the UN has really exhausted what it can do at this stage without a genuine demonstration of will."

Espen Barth Eide talks about what went wrong at the Crans Montana peace negotiations.

Espen Barth Eide talks about what went wrong at the Crans Montana peace negotiations.

Back in Oslo, Eide still reflects upon what happened around the talks table in Crans Montana.

Since then the message from the UN and Secretary General Guterres has been clear.

The UN will not make a new effort for mediating until the two sides jointly convince them that they are ready to move forward. That is more than a year and half ago.

But does Eide still believe a solution is possible?

"If both of them could listen and say, 'here is what remains, you do this, I do this', I think they could very easily come to a solution," he says.

"What makes me hesitant is that every year that goes by, is one year longer since they were one country, more people have been born into the division and more people who experienced the history have died."

It is clear the failure of Crans Montana remains with him.

"Sometimes a peace process can be an insurance against a settlement," he says.

The New Year snow has just settled outside on the cold streets of Oslo. Leaving parliament and Espen Barth Eide's office one thing is clear, he is certain Cyprus missed the opportunity of a lifetime in Crans Montana.

"The tragedy of Crans Montana is precisely that we were so close."

THE FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

Northern Cyprus has been under several embargoes since they declared their independence in 1983. Turkish Cypriots have been banned from international sports championships, locked out of the free market and isolated from the benefits of the booming tourism in the South. Have the Turkish Cypriots been forgotten by the international community?

The unrecognised flag of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

The unrecognised flag of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

After the economic destruction of the war in 1974, the Greek Cypriots in the south received heavy subsides from the international community to help develop its economy. Meanwhile, the Turkish Cypriots in the north only received financial support from Turkey and minimal aid from the rest of the world.

Backstreet in Kyrenia, North Cyprus.

Backstreet in Kyrenia, North Cyprus.

This caused less development on the northern side of the border. While tourism and business was booming in the South, the Turkish Cypriots found themselves struggling and dependent on Turkey.

Due to the declaration of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, strict embargoes were enforced as a political mean.

The economic embargo prevents foreign cash flow, and it has restricted the tourism industry, agriculture, foreign trade, sports and cultural exchange.

In 1992, a huge court-case in the European Court of Justice, saw Greek Cypriot citrus farmers successfully sue the UK Ministry of Agriculture for selling Turkish Cypriot goods. This resulted in Turkish Cypriot goods being subject to an additional 14% duty and cargoes being immediately turned back to European countries, causing serious harm to the Turkish Cypriot economy.

Exporting citrus fruit across the world acts as a pillar of the Cypriot economy.

Exporting citrus fruit across the world acts as a pillar of the Cypriot economy.

Today the embargo mostly remain.

There are still no direct flights to North Cyprus. Travellers are forced to change flights in Turkey or cross the border from the South.

Ercan International Airport saw a 400% decrease in customers in 2017 due to strict new security measures imposed by the UK department of transport questioning its status. Passengers travelling between the UK and North Cyprus were forced to disembark with their luggage in Turkey, and go through new security checks before embarking a new plane.

Turkish Cypriot athletes are still not allowed to participate in international competitions, and the Olympic Committee bans Turkish Cypriot independent athletes for competing in the games under the Olympic flag.

Furthermore, The Republic of Cyprus deem any business conducted in the north illegal, causing international bands and artists to be unable to perform there. Jennifer Lopez was famously forced to cancel her scheduled performance in North Cyprus in 2010 following extensive campaigning from Greek Cypriots.

Clothes hanging to dry in old town north Nicosia.

Clothes hanging to dry in old town north Nicosia.

Kemal Baykalli was the Deputy Secretary General for the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce for five years between 2012 and 2017, and is now an active peace activist for Unite Cyprus Now. He is one of those who believe a solution to the Cyprus problem will economically benefit both sides of the island.

Kemal Baykalli, former Deputy Secretary General of the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce, says a resolution will economically benefit the whole island.

Kemal Baykalli, former Deputy Secretary General of the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce, says a resolution will economically benefit the whole island.

However, not all Turkish Cypriot are as positive towards a unification.

Ersin Tatar is the president of NUP (National Unity Party), the largest political party in North Cyprus. In the next presidential elections coming up in 2020, he has big ambitions of replacing current President Mustafa Akinci as the leader. He does not believe that a unification with the Greek Cypriots will benefit his people, and argues that the only right solution would be to have two separate states within the EU.

Ersin Tatar, Leader of the National Unity Party (NUP), says a two state solution is the only right choice from North Cyprus.

Ersin Tatar, Leader of the National Unity Party (NUP), says a two state solution is the only right choice from North Cyprus.

The people affected the most by the economical embargoes is the average Turkish Cypriot.

ÖMRÜM'S STORY

Ömrüm Aki is one of the young Cypriots that have suffered most under the embargoes on her home country. After years spent completing her degree as an engineer, but with no industry to apply her skills, Ömrüm was forced to change direction, leaving behind her dream career in order to make a living for her two young daughters.

Ömrüm was born in Turkey in 1982 to a Cypriot mother and Turkish father, and raised in Kyrenia, North Cyprus, where she has spent her entire life since. She had a happy childhood on the island, and despite growing up with the division, she never realised the impact her ethnicity and zip code would have on her future.

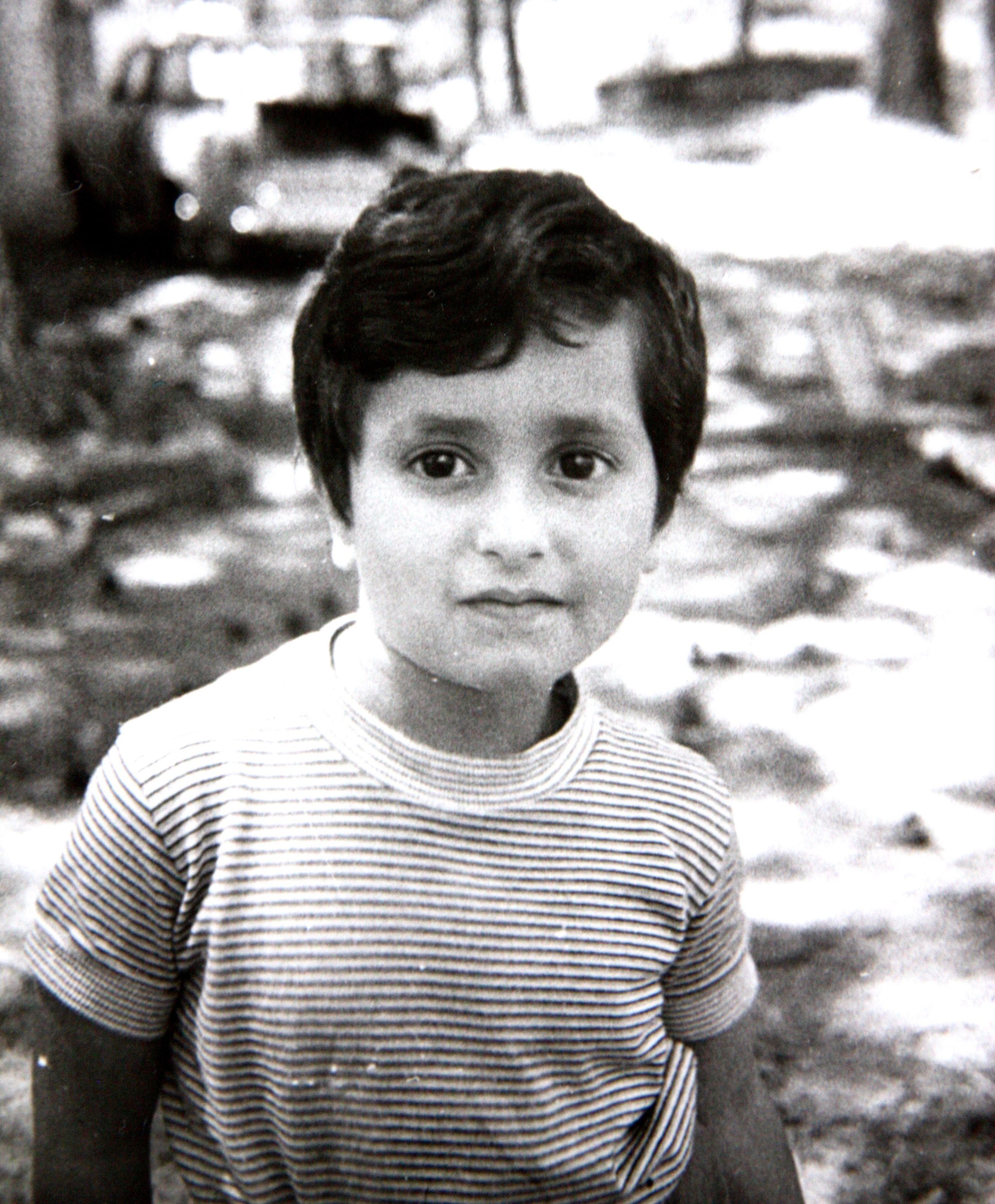

Old family photograph: Ömrüm in 1984.

Old family photograph: Ömrüm in 1984.

When she was only one year old, North Cyprus was be put under strict international embargoes that made the economy suffer greatly. Suddenly her home was only accessible to the international community through Turkey, with all direct flights and postal services being restricted. Popular international products and shops disappeared, and her favourite singers were banned from performing anywhere on her side of the border.

"We didn't grow up with hatred, but we always thought we weren't wanted."

When it came to choosing a university, Ömrüm knew she had to get out, and decided to take her degree abroad.

Every year thousands of young Turkish Cypriots move to countries such as the UK, Turkey, Australia or the United States to take their university degree, in the hope of establishing a more secure future for themselves, and with an aspiration to experience the world that they so far had lost out on.

Ömrüm spent four years in Turkey studying engineering. She had always been a smart girl, and finally it seemed she had found the perfect path for her. However, her dreams would be short-lived.

"The island being divided had a lot of impact on what I could do as an adult."

She moved back home as a proud engineer, only to find her dreams had been crushed as infrastructure in North Cyprus had come to a standstill. Suddenly the degree she had spent four years slaving over was rendered pointless. With no development on the horizon, Ömrüm was left with no job, no money and no other option than to go back and earn herself a new career that would allow her to live in the country she loved so dearly.

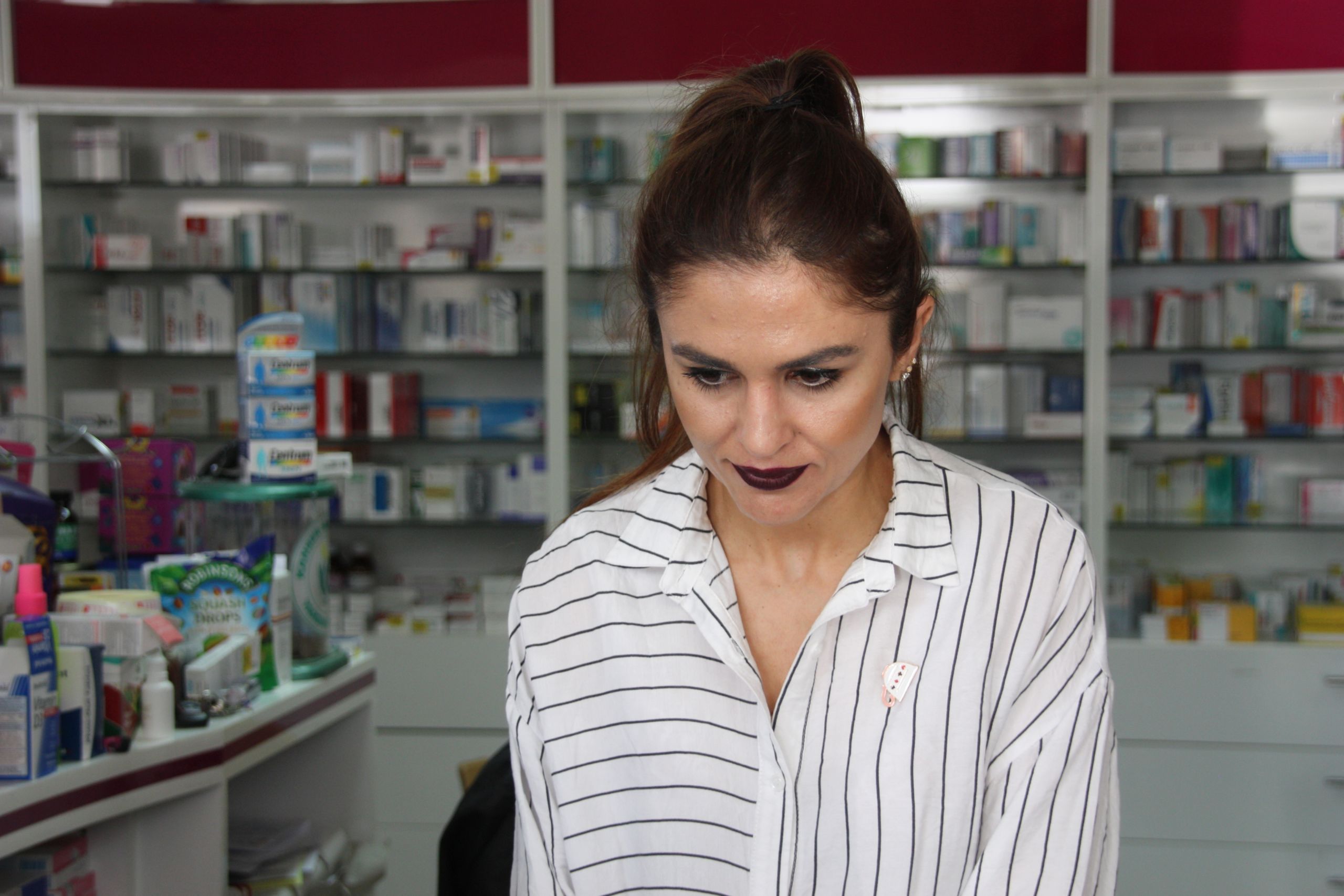

Ömrüm together with her husband Recep. They are both pharmacists and run their business in Esentepe together.

Ömrüm together with her husband Recep. They are both pharmacists and run their business in Esentepe together.

Pharmacy became her second choice, and after another four years of studying hard, this time at a Cypriot university, Ömrüm completed her second degree.

"I could't really find work as an engineer, so I had to go back to university."

Today she owns her own business, running a pharmacy near the village of Esentepe. Despite the situation having improved in North Cyprus over the past ten years with new tourism developments, Ömrum is still tied to Turkey in order to make her business thrive. Everything she sells in her pharmacy, from make-up and skincare to prescribed medicine, has to go through Turkey, each order being heavily taxed by customs.

"We just want to be acknowledged. Right now it is like we don't exist."

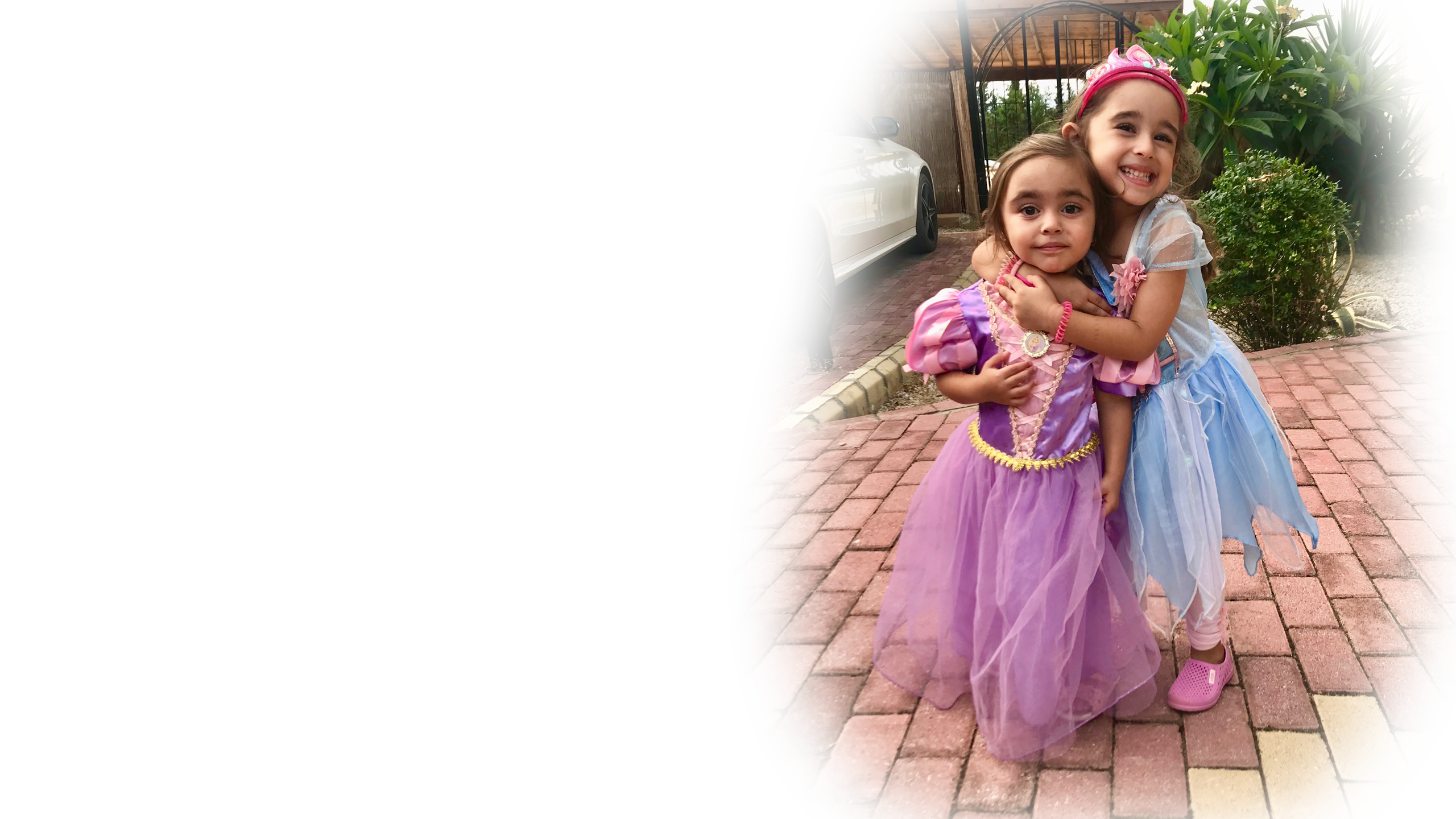

Despite hard business, today the most important part of Ömrüm's life is her two beautiful daughters, Mira (5) and Maya (3).

The centre of Ömrüm's universe: her two daughters Maya (left) and Mira (right) in 2016.

The centre of Ömrüm's universe: her two daughters Maya (left) and Mira (right) in 2016.

She describes her daughters as the love of her life. Despite growing up in the same setting as their mother, unknowing of life without a division, the girls are full of laughter and childlike imagination. They love dressing up as their favourite Disney princesses, Rapunzel and Elsa, drawing and playing, and Peppa Pig is their big hero.

Their smiles is what keep Ömrüm going when she worries about the political situation on the island. After peace talks fell through yet again in Crans Montana in 2017, there are few signs that the embargo on North Cyprus will be lifted anytime soon.

Mira dressed up as Princes Rapunzel playing with her new Peppa Pig playset.

Mira dressed up as Princes Rapunzel playing with her new Peppa Pig playset.

She often finds herself worrying about their future on the divided island. Will they face the same challenges as she did? Does northern Cyprus hold a future for them?

"Some days it is impossible not to worry about their future. I don't know if North Cyprus holds a future for them."

Ömrüm with her youngest daughter Maya.

Ömrüm with her youngest daughter Maya.

"We deserve to

to be recognised"

Ömrüm Aki

CYPRUS TOMORROW

ANDONIS AND OZEL PART II

"I saw in my dream that you would be back."

Thirty years have passed since Ozel fled to the North in the trunk of a car in 1974. Thirty years where the two communities have lived apart, unable to visit their old homes, lives and friends. In that time much has changed.

...

Ozel is driving towards his old hometown Limassol with his wife and daughter Esra for the first time. After nearly thirty years the borders between the North and the South have finally opened. The last time they were here Esra wasn't born yet. She has never heard the story he is about to tell her.

"I want to find Andonis," he says determined. His daughter, a newly educated journalist, eyes him curiously. "Who is Andonis?"

Ozel tells her the story that he for so long has hid in his heart: the story of the Greek Cypriot soldier who saved his family's lives.

As they arrive in Limassol he is struck by nostalgia. His beloved hometown has changed a lot since he was last there. He doesn't know where Andonis is now, or if he is even alive. The only thing he remembers is that Andonis' father used to own a supermarket. He never knew his family name.

They enter the local kafenion where the old men have gather to play backgammon.

"Can someone help me? I am looking for a man called Andonis. We used to be old friends."

"Andonis!" An old man throws out his arms and gets up, "I know who you are looking for. Let me take you to him."

Finally they arrive at the house they are looking for, the old man enters, and yells: "Andonis, I have some Turkish Cypriots who are looking for you!"

Without seeing who is at the door, a familiar voice yells back "Ozel, I knew you would come!"

As Andonis reaches the doorway, the two men take a second to just look at each other. The last time they met they never would have dreamt this day would come.

"I saw in my dream that you would be back," Andonis says holding back tears, "I had the same dream four times. This is a dream come true."

Then they embrace.

"You lost your hair," Ozel says laughing in between the tears. "And you got fat," Andonis replies tapping his big belly. Despite 30 years apart, it is as if no time has passed at all.

The old friends spend the day talking and reminiscing about all the good memories of the past.

...

"This is the best day of my life in the last 30 years," Ozel says as the family cross the border to go home to the North. He is bringing with him his favourite bottle of Cypriot wine and a camera full of memories.

A lot has changed. His old family home where he grew up has been bulldozed, replaced by tall apartment buildings.

"I feel like I have lost my childhood. That house is gone, taking with it all my memories," he says. But then he remembers what Andonis said before they left:

"We waited for peace for 30 years Ozel. We can wait another two or three."

You can read Ozel's daughter Esra's own memoir of their return to Limassol and the search for Andonis here.

Ozel with his wife Yuzel and Andonis in Limassol in 2003.

The old friends have crossed the border almost every weekend since their reunion.

45 years after Andonis saved Ozel's life, the two remain close friends. Despite everything, they never stopped believing in peace.

Today Cyprus still remains divided, and with the breakdown of peace talks in Crans Montana in 2017, the hope of a unification seems to fade more day by day. It is a conflict that the best mediators in the world don't seem to hack, but could the Cypriot people themselves hold the key to its solution?

Every day hundreds of Turkish Cypriot children cross the border to Nicosia to attend private schools. For many it is a choice of their parents, who worry that the education available to them in the North will hold them back. Some parents spend up to four hours a day driving their children to school, while other children, fortunate enough to live in the city, cross the border on foot.

Cecil Kayim is one of them. Every morning at 7AM she has to show her identification papers and cross the border of the divided city. She walks fifteen minutes, crosses the border and continues the journey to school on a local school bus in the South. It makes her sad that many of her Greek Cypriot friends are forbidden by their parents to visit her at home in the North, and even though she is only 12 years old, she is very much aware of the hostility from some of the people she meets. In school they don't learn anything about the war that divided their island, something Cecil thinks is good.

Cecil Kayim, 12, worries what will happen if children are taught about Cyprus in school.

Cecil Kayim, 12, worries what will happen if children are taught about Cyprus in school.

"You can't meet with your friends, because they live on the other side of the border."

Despite no promise of new negotiations, some Cypriots still cling to the hope of a united future.

Andromachi Sophocleous, 30, is one of those working for peace. Having grown up in the divided city of Nicosia as the daughter of a Greek Cypriot refugee from Famagusta, she always knew she wanted to make a change.

After studying abroad she returned to Cyprus to establish the Cypriot Puzzle, a bi-communal news project that aims to inform both sides on what is really happening on the island without a political bias. She is an active peace activist for Unite Cyprus Now, and in 2017 she went to Crans Montana to call on the Cypriot leaders to come home with a deal.

"Any activist working for peace in Cyprus has encountered criticism," she says. "We are called traitors all the time. We get attacked on social media and by mainstream media."

During the Crans Montana negotiations, then 28-year-old Andromachi was slated in the media at home for her activism. For weeks a cartoonist would make insulting illustrations of her and her big hair.

"I believe the apathy among the public is one of the reasons we can't move forward."

When peace talks collapsed two years ago, it was a big defeat for Andromachi and her friends, and she says she is no longer hopeful for the future.

"You can never have peace until you understand what you did," she says.

There are still no formal peace talks on the horizon, but the Cyprus problem is what keeps Andromachi going.

"They wanted to convince us that the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots could not live together, but I have no intention of letting them win."

Andromachi at the Home for Cooperation, 2019.

Andromachi at the Home for Cooperation, 2019.

On the other side of the border similar heartbreak is felt over the lack of progress in finding peace.

Turkish Cypriot Esra Aygin, 39, clearly remembers the day she returned to Limassol with her father Ozel, and how the usually cheerful man broke down crying at the sight of his childhood home demolished and gone.

"Everyone suffered," she says, "but unless we are exposed to it, we will never understand."

When Esra decided to become a journalist she knew she wanted to work in Cyprus, and she started her career covering the lead-up to the Annan Plan. Since then there have been a lot of disappointments.

Every time the country came close to a solution she would get excited and hopeful, only to be left heartbroken and defeated time after time.

After years of covering the negotiations, she is certain that the key to the problem lays in education.

"We need to start talking about peace to the children. They are the ones that will take the agreement that we may reach and make it possible," Esra says. "Why are no one concerned about that?"

She no longer believes in a unification, and often thinks about taking her children and moving abroad. Her beloved Cyprus no longer represent the future she dreams about.

After years of hope, it seems Esra is reaching the end.

Esra Aygin recently began working for Reporters Without Borders covering the Cyprus problem.

Esra Aygin recently began working for Reporters Without Borders covering the Cyprus problem.

...

Today the two women still work for a solution.

Through the love for their island they have become close friends, working together for peace. They come from different sides of the border, speak different languages and live different lives. But despite the many things that divides them, what unites them overcomes everything.

Andromachi still works at the Cypriot Puzzle informing Cypriots about the war that divided them and actively participates in peace activism.

And though Esra is not as hopeful as she once was, she became the Cypriot correspondent for Reporters Without Borders in February, working against the tide to tell the tale of the war the world has forgotten.

"The children are

the key to the

solution"

Esra Aygin

"Fear paralyses

our logic, but we

are far too small

to be divided."

Andromachi Sophocleous

It is unclear whether peace talks will resume in Cyprus.

Cypriots from both sides of the border remain conflicted on whether a solution will ever come to their torn island.

Calling all Cypriots! 📢

— Isabel M. Eidhamar (@isabel_eidhamar) 11 March 2019

I am currently working on an online documentary about the Cyprus Crisis and the UN, and would love to hear what YOU think!

Do you believe a solution is possible? And what kind of negotiated deal would you agree to?

Tweet me your opinion!#CyprusCrisis pic.twitter.com/8BbvKbRVn3

On July 31st the UN will decide whether their presence is still needed in Cyprus, where peace negotiations have reached a standstill.

But after 45 years as a divided island, will the Cypriots be able to put the past behind them and live together again?

THANK YOU

A huge thank you to the many incredible people who have made this online documentary possible. To the many photographers and politicians, soldiers and museums, the UN and diplomat Espen Barth Eide, not to mention the many wonderful Cypriots I have met along the way who have allowed me to share their intimate and personal stories. THANK YOU. Telling your story has been my privilege.

A special thank you to my loving and supportive parents, Gunn Eidhamar and Kim Müller Madsen, who have driven me to interviews, motivated and inspired me throughout this process. This would not be possible without you.

Credits

Produced and created by Isabel Müller Eidhamar

Contributors:

Orhan Atasoy

Dimitris Nickolas

Esra Aygin

Espen Barth Eide

Ömrüm Aki

Andromachi Sophocleous

Aleem Siddique

Willy Lindh

Cecil Kayim

Kemal Baykalli

Ersin Tatar

The United Nations in Cyprus, UNFICYP

Photography:

Turkish Woman Mourning the Death of her Husband, Cyprus, 1964 © Don McCullin, Courtesy Hamiltons Gallery London

Richard Chamberlain

Roman Robroek, https://romanrobroek.nl/

Katarina Záhorská / UNFICYP

United Nations, UN News

Including personal photographs from Ömrum Aki, Willy Lindh, Orhan Atasoy, Dimitris Nickolas, Cecil Kayim and Esra Aygin

Music & Sound Effects:

Alan Spiljak, Clouds

Alan Spiljak, Light Blue

Alan Spiljak, Empty Days

Alan Spiljak, Something wonderful

Alan Spiljak, Time

Alan Spiljak, New day

Alan Spiljak, Dreams

Alan Spiljak, Spring memories

Meydän, Glimpse of eternity

Meydän, Contemplate the stars

David Hilowitz, Time passing

Poem:

Nese Yasin, Yurdunu sevmeliymiş insan (One has to love his/her country)